Inspired by the true story of Patricia McCormick, The Moment of Truth tells the tale of the first American woman to professionally bullfight. Set in the early 1950s, it follows Kathleen Boyd as she drops out of art school to pursue her dream of fighting bulls in Mexico. Confronted with a disapproving mother and fiancée, and, later, a controlling and greedy manager, Kathleen must decide how much she is willing to sacrifice to make it as a matador.

Written in assured prose, The Moment of Truth is fast-paced and gripping, telling a good story while illustrating the courage it takes to buck society’s expectations.

We’re delighted to discuss The Moment of Truth with its author, Damian McNicholl.

Kelly Sarabyn: Thank you for joining us. Telling the story of the first American woman bullfighter is such an interesting premise. What drew you to this subject? How closely did you intend the character Kathleen Boyd to resemble Patricia McCormick?

Damian McNicholl: Thanks for inviting me.

I came across a compelling article in the New York Times about Patricia McCormick’s death and I found her life fascinating. She was born in Texas and left for Mexico in her twenties to become a female matador in an age when bullfighting was singularly male. Ms. McCormick grew up in an era when girls were expected to train for traditional women’s jobs, teachers, nurses and secretaries, and then give them up after marriage. Being a housewife became their job.

Kathleen Boyd is feminine and pretty like Patricia McCormick, but her story is not Mc Cormick’s. For the purposes of the novel, I had to create scenarios that McCormick may never have faced in order to tell the story and show the bigotry and sexism she encountered.

KS: What was your research process like? Not only were you writing about the specific cultural activity of bullfighting, you were writing about the 1950s in Mexico and America, both of which have their own distinct cultural mores that differ from the ones we have today. How did you ensure you’d have all the details right?

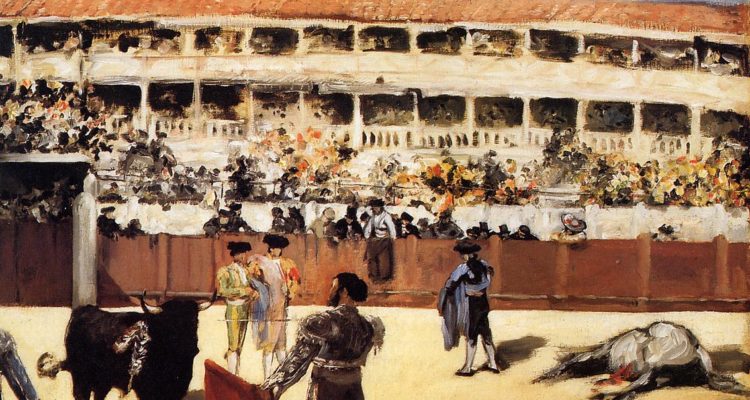

DMN: The research was rigorous and took me a year. The fact I’m an attorney helped greatly as I was already used to skimming through vast amounts of material to get the information I needed. I knew little about bullfighting or 1950s Mexico and the US, but that was part of the fun and made the writing exciting. Losing myself in the period, discovering the foods people ate back then, the cars they drove, what towns, bullrings and businesses looked like in Mexico and the US, how matadors might fall in love and have a relationship, each discovery helped to make the story real and believable. After I finished writing the novel, I knew how to execute the various passes the matadors perform, and how they approach the bulls and use the cape and muleta [stick with red cape]. I also had help from experts in bullfighting who spotted any mistakes I made in the descriptions and am indebted to them.

KS: I was surprised that Kathleen encountered a number of people who thought bullfighting was wrong and immoral. She even lived with a woman who was a vegetarian. How common were animal rights advocates in the 1950s in Mexico and America?

DMN: The concept of animal rights was not developed as it is today. The Humane Society existed in the 1950s but concentrated its efforts mostly on protecting abused dogs and cats. There were no groups protesting at bullfighting arenas throughout Spain, Portugal, France, Mexico and other Southern American countries where it took place. In those countries, bullfighting was regarded as art as much as a sport and the matadors were treated like celebrities.

There were vegetarians in the 1950s and people who believed bullfighting was wrong, but they were a silent minority then. Indeed, bullfights where a bull is killed were banned in the US. Only bloodless bullfights were allowed and still occur today in Texas and certain areas of California. I do want to add that I believe strongly that animals have rights and abhor any form of cruelty to them.

KS: After Kathleen’s roommate claims it is immoral to kill a bull for sport, Kathleen responds, “Bullfighting’s not a sport. It’s art. Theater.” Throughout the book, Kathleen’s approach to bullfighting is very artistic, and she believes the bull is participating in the performance with her. While this is compellingly depicted, I think to many modern readers, it is hard to accept killing an animal could be art. Were you able to view it that way? Despite her confident words, Kathleen still seemed to struggle with the act of killing the bull. In your mind, was her difficulty from a natural revulsion to killing, from her respect for the bulls, or from something else entirely?

DMN: It’s very important to understand the novel is historical. It’s set in the 1950s when bullfighting was viewed very much as an art form as well as sport. It was considered an intricate dance between the matador and the bull wherein the matador brings the horns closer and closer to the body until the bull literally curls around it like a cloak. My research verified that this was how it was viewed and, indeed, Ernest Hemingway describes the fight in terms of art in his books. Today, of course, the vast majority of people see it as bloody and cruel. But there are many aficionados in countries where bullfighting takes place today that still see it as theater rather than sport.

As the writer telling the protagonist’s truth, I had to set my personal opinions aside and view the fight as the heroine viewed it. Otherwise the writing would have been stiff, wooden and deficient. My heroine viewed the fight as part art and part theater and I believe she did have a natural instinct toward revulsion when the time came to kill the bull in the final act. That’s why her trainer is very harsh with her in a particular scene when she commences her training. Kathleen does indeed love and respect the bulls she fights. Her grief is genuine and deep on the death of a courageous bull, which is why she kneels and honors some of the bulls at the end of her fights.

KS: One of the current conversations in the literary world is the issue of cultural and identity appropriation in fiction. Some minorities and women feel that it is problematic for dominant groups to write from the perspective of traditionally oppressed groups. The New York Times wrote a good summary of these concerns, in response to a speech Lionel Shriver gave criticizing the idea. Shriver argued these kinds of limitations controverts the whole purpose of fiction. As a male who wrote a main character that is female, and a non-Mexican who wrote Mexican characters, what are your thoughts on this debate? Was writing a female character different from writing a male character, and if so, how? Did you feel you had to guard more carefully against falling into stereotypes when writing from the perspective of a character with a different gender and culture?

DMN: I think it’s ridiculous to hold, for example, that a heterosexual woman should not be allowed to create a protagonist who’s male and/or gay and/or transsexual because it could be seen as appropriating a minority culture. I think it’s ridiculous to hold that a white man can’t create a female protagonist who’s Mexican and/or black and/or lesbian and/or disabled. Fiction is about creating and I agree with Shriver that authors should not be constrained by expedient political correctness. So long as the author does his or her research and due diligence, I think it is absolutely permissible to create characters from different ethnicities and backgrounds and/or write from the point of view of disabled people, etc. It will be the reader who decides whether the novelist has been successful or not at depicting the minority culture or group, etc.

Writing a female character was different to writing a male character, of course. Male and female characters respond to situations, experiences and other people differently and this must be depicted in the work if it is to be credible. I’ve written female characters before, though. Kathleen is not my first. In my debut novel, A Son Called Gabriel, I depicted Gabriel’s mother and aunts in great details. To write a female character, I rely on a combination of my experience living in a house with a Mom and two sisters, the great literature by men and women who’ve written about the opposite sex, and my instinct.

KS: You chose to structure the book by writing most of the chapters in the first person, from Kathleen’s perspective. But you also included some chapters in the third person, from Kathleen’s manager Fermin’s perspective. As a reader, I appreciated the added insight into Fermin, as he clearly only showed one side of himself to Kathleen. Why did you decide on this structure? Did you consider writing Fermin’s chapters in the first person, for example, or including other characters’ perspectives?

DMN: I always saw Kathleen unfurling in the first person. It was her journey and I had a very clear picture of who she was, her flaws and what she feared and wanted to achieve from the get-go. When she came to me, she was extraordinarily well-developed in my mind as a character and I knew her voice. I like to experiment as a writer and didn’t want to write Fermin in the first person. He is a complex character, a bit of a chauvinist but also a man with deep-seated conflicts who loves his wife and family, and I felt the best way to show these facets to the reader was to write him in third person. The only other person I thought about giving a point of view in the novel was Kathleen’s lover, Julio. I examined the pros and cons and finally decided it wasn’t necessary and that doing so might even dilute some of Kathleen’s experiences, both in the bullring and intimately.

KS: For the most part, the men Kathleen encounters are misogynistic and controlling. In two cases, they are even violent. Is this just a reflection of the times, or was the behavior driven, in part, by a backlash to Kathleen’s bucking of traditional gender roles? Fermin, her manager, is generally misogynistic, but he seems to vacillate between treating her as a man while he’s training her as a bullfighter (“Which are you, Kathleen? Woman or bullfighter?”), and as a woman to be controlled and managed. How would you describe Fermin’s views of women, both generally and as they applied to Kathleen?

DMN: It’s correct that not all the men whom Kathleen meets behave this way. She befriends Julio early on in the novel and he is immediately helpful and their relationship develops into an intense love affair. Also, her sponsor Mr. Barros is like a father figure and Patricio, her confidential advisor, is very supportive and encouraging. The first apprentice she appears with in the bullring is friendly and not at all threatened by the fact she’s a women in what is seen as a man’s role.

As an antagonist, Fermin is a complex character with many layers. He loves his wife and at the same time is also critical of her. He expects her to be an obedient housewife and do his bidding and, yes, he reacts violently when he believes she has been disloyal or wronged him. His past history in the bullring and perceived mistreatment by peers has warped and driven him to seek revenge and Kathleen, rather ironically, becomes the means to that end. He tries to ignore her gender by treating her like a man and at the same time realizes, if he succeeds in making her famous, that he has proven a woman can do what his male peers can do and thus he’s obtained the ultimate revenge. I think Fermin is representative of men of that patriarchal era where women were expected to behave deferentially. He feels threatened by women who assert themselves and feels a need to control them, but he does not despise or fear women as some men do. I think Fermin has a love-hate relationship with Kathleen and this drives him to control her despite his needing her to succeed.

KS: There are many different, complex relationships in the story, but the dominant one is between Kathleen and Fermin. Fermin has his own messy history with bullfighting, and while he enables Kathleen’s dream of bullfighting, he also unduly controls it, seeking to mold her in his image, and use her for his own fame and fortune. How do you think this relationship affected Fermin and Kathleen? Did the relationship ultimately change them for the better, or the worse?

DMN: Fermin and Kathleen, and to a lesser extent Julio, form the heart and central conflicts of the novel. Through their characters, the story explores issues of bigotry, chauvinism and gender inequality. It’s not a novel about bullfighting at all. It’s a novel about one woman’s difficult journey to prove she can be the equal of any man in a career traditionally associated with men. Fermin and Kathleen’s relationship change profoundly as the story unfolds. At the beginning she worships him and she’s so ambitious that she is willing to address him as ‘Maestro’ at all times, as he demands because he has been a famous matadors. She is fearful, has much to learn and is naive about his controlling ways. Kathleen is also young, a nineteen-year-old when the story begins, and does not see Fermin has huge ambitions nor the part she will play in his obtaining the recognition he feels has been denied him. Gradually her eyes are opened and she challenges him.

KS: Kathleen experiences a number of tragedies over the course of the book, starting with her father dying when she is child and her mother becoming aloof and distant in response. I won’t list the other tragedies as I don’t want to give away too much, but suffice to say Kathleen is dealt — and perhaps attracts — a number of hardships. In your mind, is there a connection between the loss and loneliness of Kathleen’s childhood and her determination to strike out on her own, against all the odds? Does seeking to live an unconventional life make you vulnerable to tragedy and loss?

DMN: That’s a great question. I think Kathleen was always independent-minded as a child, was content in her own company and didn’t need to be surrounded by friends. She enjoyed art, reading and learning Spanish from the woman who cleaned their house and had no interest doing the things that teenage girls did in the 1950s. Spending time alone as a girl allowed her to mature and get to know her likes, dislikes and strengths and know very quickly what she wanted out of life and to go after it, though she didn’t expect to encounter as much opposition and sexism as she did. As the novel shows, it was not by accident that she enrolled at a college in an American border town. The loss of her father, who instilled in her the confidence that she could do whatever she wanted to do in life, was profound, and I think his influence gave her a toughness and determination that allowed her to pursue such an unusual career. It was his taking the family to the bullfight when Kathleen was a very young girl that instilled in her a love of the bulls, to the extent she returned to Texas and practiced passes with an old towel on the family dog much to her mother’s chagrin.

Living an unconventional life certainly carries risks. Trailblazers and people choosing to march to the beat of different drums, whether willingly or not, expose themselves to the consequences of behaving outside the status quo. They expose themselves to the ridicule and anger of the dominant culture and often suffer hardships as a result. This always happens, but it needn’t necessarily result in permanent tragedy or loss. As with all things, society changes. For example, what was regarded as an unacceptable career choice for women in one era becomes perfectly acceptable in another, and this often leads to a new status quo. Not many question female pilots, astronauts, truck drivers or plumbers anymore.

KS: Very true. Thank you for joining us!

Damian McNicholl was born and raised in Northern Ireland and worked as an attorney in New York City. His critically acclaimed first novel, A Son Called Gabriel, won awards and recognition, including an ABA Booksense Pick, a Foreword Magazine Book of the Year Finalist, and a Lambda Literary Awards Finalist in the debut novel category. Visit him at www.damianmcnicholl.com. You can buy The Moment of Truth here.