Historians and historical novelists have a lot in common.

We both love the chase, the research.

Tracking down that nugget of information that is so telling, so revealing of the time or the character or the event gives us chills.

We’re willing to go down endless rabbit holes to figure out how much a worker was paid a couple of centuries ago and what that would buy him.

We delight in stumbling over old maps that reveal a city or the countryside as it was before modern roads and urban improvements.

And a cache of letters by our historical subject—or someone very like our fictional protagonist? Pure gold.

We differ in some fundamental ways, however. As both a historian (Yale Ph.D.) and a historical novelist, I’ve thought a lot about these differences and how they affect our approach to the work. I think perhaps it boils down to three things:

- Novelists pursue universal truths while historians look for verifiable facts.

- A novelist looks for a story arc, whereas a historian looks for what’s missing and tries to fill it in.

- A novelist sees the empty spaces where documentary evidence doesn’t exist as opportunities for invention, while a historian sees them as opportunities for further research.

Each of those differences could be the subject of a meaty article, but what interests me most are the empty places, the dead ends, the gaps in information that hold frustration for the historian—and endless possibilities for the historical novelist.

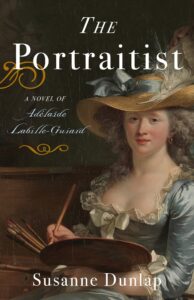

I’ll use my forthcoming novel The Portraitist as an example. My historical protagonist, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, is one of the two most important women artists in Paris in the period surrounding the French Revolution. The other one, Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, is by far the more well known, having produced somewhere around 600 canvases over the course of her long life, been Marie Antoinette’s official portraitist, and written a three-volume memoir in her eighties.

By contrast, Adélaïde’s extant output numbers are probably fewer than a hundred works. Plus, the only record we have of anything she wrote is a couple of letters relating to legal matters. We also know nothing about her very early training. Only what happened once she was already fairly accomplished. And there’s no information about what she died of at the age of 54 or where she is buried, and nothing to elucidate what led her to her disastrous first marriage and how exactly it ended.

By contrast, Adélaïde’s extant output numbers are probably fewer than a hundred works. Plus, the only record we have of anything she wrote is a couple of letters relating to legal matters. We also know nothing about her very early training. Only what happened once she was already fairly accomplished. And there’s no information about what she died of at the age of 54 or where she is buried, and nothing to elucidate what led her to her disastrous first marriage and how exactly it ended.

It was another gap, though, that truly inspired my book. It’s difficult to say exactly how the two artists interacted with each other, where precisely their paths crossed, and how they felt about this rivalry that was very much part of the art world at the time. Elisabeth doesn’t mention Adélaïde in her memoir, although she makes allusions to her in a mostly derogatory way, and there’s no evidence that they frequented the same social events or moved in the same social echelons.

These interstices made room for the story I have told about the underdog, the less successful and not nearly as popular Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. I was free to imagine how their rivalry played out.

I could shade in the nuances of character and motivation so lacking in the historical record.

Although the two women exhibited in the same salons, had royal commissions that would have necessitated going to Versailles and were elected to the Académie Royale in the same year, to my knowledge, there is only one documented occasion when they were in the same place at the same time. That was in 1802—long after the Revolution and the year before Adélaïde died. They both attended a dinner party given by the American painter Benjamin West in Paris.

What the historical facts gave me—most importantly—were the starting and ending points of my story. I started with the first salon, where they both exhibited and ended with the aforementioned dinner party. What comes between is a thread of inferences, emotions, triumphs, and failures that link all the historical actualities into a cohesive whole.

The gaps in Adélaïde’s biography allowed me to mold her into the protagonist I needed to bring the volatile period, the Parisian setting, and the art world to life. If my book not only takes readers on a voyage of discovery but also encourages people to seek out Adélaïde’s work in museums around the world, I’ll feel I’ve accomplished something important.

In fact, the historian in me will be just as happy as the novelist.

In fact, the historian in me will be just as happy as the novelist.

Susanne Dunlap is the author of twelve works of historical fiction for adults and teens, as well as an Author Accelerator Certified Book Coach. Her love of historical fiction arose partly from her studies in music history at Yale University (Ph.D., 1999), and partly from her lifelong interest in women in the arts as a pianist and non-profit performing arts executive. Her novel The Paris Affair won first place in its category in the CIBA Dante Rossetti Awards for Young Adult Fiction. The Musician’s Daughter was a Junior Library Guild Selection and a Bank Street Children’s Book of the Year and was nominated for the Utah Book Award and the Missouri Gateway Reader’s Prize. In the Shadow of the Lamp was an Eliot Rosewater Indiana High School Book Award nominee. Susanne earned her BA and an MA (musicology) from Smith College and lives in Biddeford, Maine, with her little dog Betty.