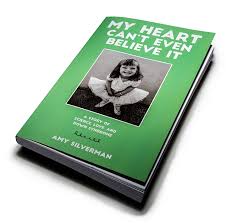

As a journalist, Amy Silverman works with words in order to make a living. She is a journalist, blogger, and NPR contributor. Her latest writing project is a searching, compassionate and ultimately uplifting memoir about the emotional and educational journey that ensued after her baby was diagnosed with Down syndrome. Silverman documents a multitude of challenging life lessons that ultimately put her experience into perspective. In this exceptionally well-written memoir, Silverman weaves a story of her life with her daughter Sophie that is truly transformative. She writes with warmth, confidence, but most importantly, with purpose. Her goal is to empower and educate others. Oh, and make them laugh—because she cracks me up.

As a journalist, Amy Silverman works with words in order to make a living. She is a journalist, blogger, and NPR contributor. Her latest writing project is a searching, compassionate and ultimately uplifting memoir about the emotional and educational journey that ensued after her baby was diagnosed with Down syndrome. Silverman documents a multitude of challenging life lessons that ultimately put her experience into perspective. In this exceptionally well-written memoir, Silverman weaves a story of her life with her daughter Sophie that is truly transformative. She writes with warmth, confidence, but most importantly, with purpose. Her goal is to empower and educate others. Oh, and make them laugh—because she cracks me up.

Amy, thank you for being here with us today. And thank you for sharing such an affecting story.

Maribel Garcia: When I was pregnant with my girls, I was teaching university students about ableism, anti-racism and homophobia. So unlike people that prayed for a “healthy” child I couldn’t even bring myself to do that, because I knew that a child with Down syndrome did not fall in most people’s category of “healthy.” That said, my mentality was, I will be happy with my baby even if they will have intellectual limitations. I just knew that I would figure it out. After reading your book, I realized that I belonged to the camp of people who romanticized children with Down syndrome. I am not saying that having a child with Down syndrome is the worst thing that can happen to a person because that is the beauty and the whole point of your memoir, but it’s not all sunshine and roses.

Your honesty about your own transformation really highlighted the shift in your own thinking. You write about the attitude you initially had towards people with Down syndrome, before Sophie came along. Before you met Sophie, you used the r-word and switched lines at Safeway when you saw a bagger with special needs. You write, “People in my family didn’t have imperfect babies.” Sophie’s diagnosis was devastating news.

Memoirs are about significant stories that show what the author has learned from their experiences. They are also about telling the truth. Your story is honest and genuine—was telling the truth hard to do?

Amy Silverman: Looking back I suppose it should have been, but really it was more cathartic than anything else. I think this is because of my background in journalism, where the facts matter more than anything else. I almost didn’t consider the consequences – that I was revealing myself as a jerk, or at least would perceived as a jerk. I just really wanted to get out the truth of what happened to me, with the hope that by revealing that, I would help others by demonstrating that this kind of thing – having a baby that’s not considered perfect and having tough feelings about it – happens. It happened to me. And it’s okay. I made it through to the other side and learned so much and wish I’d known then what I know now. Although that’s life in general, right?

MG: You are so not a jerk. Baring your soul leads to a good story and you tell a great one. Your sub-title: A Story of Science, Love and Down syndrome couldn’t be more fitting. I read memoirs because they reveal the true feelings of the writer, so I did expect to find how you reacted emotionally or how you announced the news to friends and family, but I truly appreciated and benefited from the savvy journalist who provided readers with an overview of a special needs child’s educational and legal rights, and, the latest scientific and medical information on Down syndrome. In other words, the memoir wasn’t just a great uplifting read, but a great reference. What has been the reaction of your readers who have children with Down syndrome?

Amy Silverman: First, thank you for your kind words! It means so much that the book resonated with you. I’ve had some really amazing responses to the book from parents of kids with Down syndrome. I wanted to write a book that was different than what is already out there. One that is irreverent. Because it’s okay to be irreverent even though you have a kid with special needs! And conversational, the way my best interactions with other parents of kids with DS have been. And I’ve had great responses from other parents who said the book touched them and that they related to a lot of it. One of the funniest came from Eliza Woloson, who wrote my favorite kid book about Down syndrome, “My Friend Isabelle.” Woloson said that reading my book was like reading a book by David Sedaris if he’d had a kid with Down syndrome. I loved that – the best compliment ever! And I’m pretty sure I’m not worthy, but hey, I’ll take it.

That said, when she bought my book, my editor at Woodbine House said that she figured that off the bat it would only appeal to about half the parents of kids with Down syndrome, not only because I’m irreverent (there might be an F bomb or two in there) but because I’m not religious (AT ALL) and I’m vehemently pro-choice, which does not necessarily mean pro abortion. I get that and it’s a big part of why I wrote the book – to put more viewpoints out there. There are a lot of Down syndrome memoirs about perfect children. Heck, I don’t think any child is perfect. So I have a different starting point. I do think it has limited my audience somewhat. But I got to write the book I wanted to write, so I’m pleased.

MG: Memoir writing can be therapeutic, was this the case for you?

Amy Silverman: Yes it has, oddly, since I’ve always found writing to be a very painful process and as an editor I am constantly telling my writers that if it’s not hard they aren’t doing it right. Writing the book was tough but also cathartic. I find that with my blog about Sophie, as well. I walk around feeling like a balloon that’s been blown up huge and round and bursting and after I’m done writing a post I feel like the air has been let out in a good way.

Putting the book out into the world has also been therapeutic in ways I didn’t predict. I’ve never belonged to support groups or done any outreach. The book has changed my role and my attitude – at least a little bit. It’s been good for me.

MG: What prompted the urge to write a memoir? And what does Sophie think about the book?

Amy Silverman: I really did want to write the book I wish I’d read before I had Sophie, a book that reached out to people who do not have kids with special needs but maybe have a friend with a child with autism, or teach in public schools or just happen to interact with people with disabilities. Disability – but intellectual disability specifically – seems to be the final frontier in multiculturalism. We don’t know how to talk about it, let alone talk to people who are intellectually disabled. I know I didn’t know how to do either before I had Sophie. I wanted to change that in my own small way.

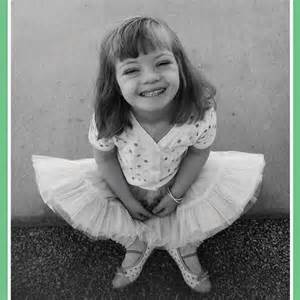

Sophie loves the fact that I wrote a book about her, and she loves to come with me to speaking engagements. She has her own issues with having Down syndrome, and some days she wants to talk about it, others not. She has not sat down and read the book (neither has her older sister) so her affection is really in the abstract at this point, but on some level I think she gets what I’m trying to do.

MG: You’re a journalist, used to telling other people’s stories, was it difficult for you to invite readers into such a personal space?

Amy Silverman: Yes and no. I had already been writing memoir for a while (not necessarily associated with my career as a journalist) and teaching memoir writing, and most important, I think, studying writers who mix journalism and memoir really well. Andrew Solomon is my favorite, author of “Noonday Demon.” He studied depression in himself and also as a journalist. Ditto for Pete Earley’s “Crazy,” in which a former Washington Post reporter responds to his son’s schizophrenic break by traveling to Florida and reporting on mental health issues in Miami’s jail system. (Hint: Conditions are not good.) So for me, mixing memoir into the story made sense. And I finally had my own story to tell.

MG: Down syndrome offers a challenge to society’s prioritizing of intellectual capabilities. Our children are more than just their intellectual capabilities. Reading your memoir made me realize how easily we forget that there are so many other human attributes. What would you tell a new parent if they asked you about this? Are we more than the sum of our parts?

Amy Silverman: Well, first, I’d tell a new parent that I really hate the term intellectually disabled. I hate it more than retarded, though I know we can’t use that one anymore and I get why. I don’t see Sophie as intellectually disabled. She learns differently than I do, but I honestly think she is far wiser. And, frankly, better at math. Really! My advice for new parents is to let their child teach them about Down syndrome. It’s different in everyone who has it. Don’t assume anything, including, “My kid can do anything!” That kind of thing drives me nuts, none of us can do “anything.” Let your kid guide you as you are guiding her.

MG: There is a highly medicalized approach to disability, like finding a cure for Down syndrome. Do you think that we will ever get to a place where the conversation changes? In other words, work towards being a society that seeks to participate in the creation of just and fair societies within which people with Down syndrome can live well?

Amy Silverman: That is a great question. Actually, no. I think as science gets more advanced and we can order up everything from eye color to height, people with Down syndrome will cease to be born. That will take a long time – we will probably ruin the planet long before that. But that’s the ultimate conclusion. It’s another reason I wrote the book. I am terrified, looking back. Like I said, I’m pro-choice. Which is fine – as long as you are educated. I was not. I can tell you for sure that if I’d known at 4 weeks that my fetus had Down syndrome, I would have had an abortion. That’s how little I knew about Down syndrome. That’s how much I would have let science guide me.

I hope I’m wrong and that there are people out there who will lead a movement to embrace those who are not perfect by society’s standards, instead of just letting science bulldoze the things that make us unique.

MG: The chapter about Sophie anticipating her period was aptly titled, “There will be Blood.” It’s also a nod to your particular kind of sarcastic humor, that I find absolutely refreshing. Your precious little girl – now a tween – wanted breasts and you had to give her “the talk.” More importantly, your little girl was entering a different stage of physical development and there isn’t a lot of information out there. It takes someone like you to write about this and inform readers about the gaps in information. You write, “The information, the help-even the interest-gradually expires as your kid with Down syndrome gets older. Babies with Down syndrome are adorable, angelic, loads of fun. Teenagers and adults? Not so much…No one would want to be around a teenager who collects paintbrushes and sucks her thumb or an adult who throws temper tantrums and wants to watch Wonder Pets.”

That said, we are not comfortable talking about sex. Period. You write, “When you have an adult son or daughter who still acts like a child, you don’t want to think about them having sex.” Eventually, these conversations will come up with Sophie; do you think that you might write about Sophie, as she grows older?

Amy Silverman: I do think I will write about Sophie as she gets older – in fact, I have already started – but it’s such sensitive territory! The most sensitive. I will not reveal all of Sophie’s secrets but I will keep writing about her and about these topics because I think it’s so important to lift the veil. In my opinion, it’s the only way life for people with disabilities will improve, and (I know I’m getting corny) it’s a way for all of our lives to improve. Mine, anyway.

Amy, thank you so much for writing such an important story and for answering our questions.

Amy Silverman: Thank YOU!