Hi Leora, welcome to Book Club Babble. If someone were to ask, who is the author behind Do Not Disclose? How would you describe yourself?

Like so many other women, I am many things – a daughter, a sister, a wife, a mother, a friend and now a grandmother. And in my careers, I was a lawyer, a judge, and now a writer and an author. All these different parts of me have come together and made me who I am, But these elements are not static, they change and evolve with time, experience and life’s many curveballs. My ten-year-old self is still with me, along with my sixteen-year-old self, but life has also given me a head and a heart beyond those years.

I always knew I wanted to be a writer. Words were always my outlet as a young reader and writer of little poems and short stories. Even at a young age, I felt that I wanted to and needed to “leave something behind,” something that would outlive me. Although I didn’t know it then, I’m sure now that this need was intimately connected to the Holocaust, which is part of my family’s legacy.

What inspired you to write your memoir? What is the story behind it?

I had a pretty normal childhood – attentive parents, school, friends, and a house in suburbia. Still, something within me knew there was something wrong, but I didn’t know exactly what. Later, I discovered that my childhood friend, my best friend, was actually my sister, and that a person I’d called “aunt” all my life had been my father’s mistress. It upended my world, but it also released me from the cloud over my childhood. The truth really does set you free.

I started writing fiction on my off-hours as a judge in Juvenile Court, One afternoon after work, rummaging around in a thrift store, I found an unusual postcard that had been written in 1942 by a British soldier. I was intrigued by the writing and challenged myself to see if I could “find” this soldier. It was 2003, the early days of the Internet, and it took me a year, but I did find the soldier who had written the postcard. Even though he had passed away, I felt that the found postcard wasn’t mine any longer and that I should return it to his family and I traveled to England to do so. When they welcomed me like long-lost kin, I thought my journey was over, but I never quite understood why I had embarked on this one-year quest in the first place.

For years the postcard story sat dormant in my head and in the journals I’d written from 2003-2004. I then remembered something the soldier’s family member told me as I was leaving England – “it’s sometimes easier to look into or research a stranger’s life than your own.” I realized that my postcard story connected to me and my family in ways I’d never thought was possible and I decided to intertwine the two stories – the quest to find the soldier and my family story together into a memoir.

What was the most difficult part of writing your memoir?

Unlike writing fiction, I was writing about people I knew, whether living or dead. I felt that I had a responsibility, to the best of my ability, to write about them with truth and compassion. Again, unlike fiction, I could not imbue these people with extra “interesting” characteristics. I had to write them as I saw them, as they were, along with the narrative of their experiences and didn’t have the luxury of using the usual “poetic license” freely. But the hardest yet cathartic part was reliving some of the difficult moments of my life and seeing them in hindsight.

How did you choose what to leave out and what to include?

I write very sparingly, so I probably left out many things. Each time I want to describe a situation, a person or a physical place, I ask myself whether this or that detail is truly important or takes away from the narrative.

I also so respect my readers and know that they can fill in the blanks of whatever I don’t include. I try not to tell the reader everything about my characters so that the reader can imagine them on their own. For me, the adage “less is more,” describes not only my writing, but also many other parts of my life.

What is the biggest message you want to get across?

I believe many families have a secret that colors their family dynamic, and the more a family secret is hidden away, the more it wants to come out, the more it has to come out, somehow, some way. Children especially, know when something is wrong. They feel it even if they can’t verbalize it or understand it. Secrets about biology, paternity or maternity are especially harmful as they go to the very core of our being – the questions we ask as to who we really are.

My message is that even after secrets are exposed, there can be redemption. The Bandaid covering up the secret is lifted and may hurt, but airing it out is the key to healing the wound. When I found out about my sister, the puzzle of my childhood was revealed. Everything that hadn’t made sense started to make sense. Who I was and what I really wanted became clearer. I guess my message is that truth is the most powerful medicine to healing.

Do you think that making meaning out of our stories is a form of therapy?

Stories are one form of therapy. They connect the random dots of life and attempt to find arcs and meaning. In life, we all crave a beginning that leads to a middle and eventually an end, and stories provide that for us. As children, we learn about humanity from the stories our parents read to us. Later as adults, the stories we read become more nuanced and complicated, but they still connect us to others whether the story is a memoir, fiction, romance or even science fiction.

What has been your biggest learning experience since you started the process?

Learning to trust myself was my biggest learning experience in this process. Most writers, whether published or not, whether a veteran or a debut writer, second-guess themselves all the time. Do I have the right words? Is the story interesting enough? Will my story resonate with other people? These questions persist from the moment one writes downs the first chapter and well past the day the book is published. These questions are important to a writer, but we must also trust in ourselves and trust our instincts.

What is your goal? The big vision of what you want to achieve by putting your story out into the world?

I hope my personal story will resonate with others. Although my family’s history was connected to the Holocaust, I believe family secrets are universal, no matter where or how a family history was forged. We are all connected by our humanity, something we often forget in a world that is often, sadly, fractured.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

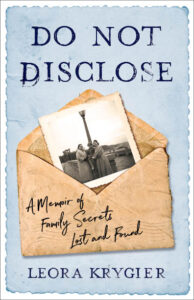

Leora Krygier is a former Los Angeles Superior Court, Juvenile Division judge. She’s the author of When She Sleeps (Toby Press), which was lauded for its “luminous prose” (Newsweek) and praised by Booklist, Library Journal, and Kirkus. It was also a New York Public Library Selection for “Best Books for the Teen Age.” She’s also the author of Juvenile Court: A Judges Guide for Young Adults and their Parents (Rowan & Littlefield) and Keep Her (She Writes Press), a young adult novel reviewed as a “vibrantly dazzling literary cocktail on the restorative powers of love.” Her latest memoir, Do Not Disclose (She Writes Press), published on 8/24/21. She lives in Los Angeles with her husband, David.

Thank you, Maribel, for this opportunity to speak with you and your audience about Do Not Disclose. Wishing everyone healthy, safe and joyful times!