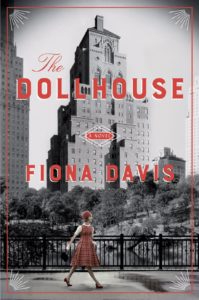

The Dollhouse is the riveting story of two American women living at the famed Barbizon Hotel sixty years apart.

In 1952, the Barbizon is a New York boarding house for aspiring models, editors and secretaries. Darby McLaughlin is there to attend secretarial school, but under the tutelage of a Barbizon maid, she is swept into a dangerous night life.

In 2016, the Barbizon has been converted to condominiums, but a few of the 1950s women are still living there in rent-controlled apartments. Rose Lewin hears rumors about Darby’s dark past, of Darby being slashed by a knife and the Barbizon maid falling to her death. A journalist whose own life is in disarray, Rose decides to investigate her reclusive neighbor.

Effectively switching between the past and the present, The Dollhouse tells the story of two women struggling to define themselves, their friendships and their careers. It illustrates not only all the things that have changed for women, but also those that have stayed the same.

We are happy to discuss The Dollhouse with its author Fiona Davis.

Kelly Sarabyn: The Dollhouse intertwines the story of two women, Darby, living in the Barbizon Hotel in 1952, and Rose, at the Barbizon (converted to condominiums) in 2016. Rose meets Darby and becomes intrigued by her and the dozen or so other women who have been living there for over sixty years. As Rose investigates Darby’s story, we also see it unfold in its own time, in 1952. This is an intricate structure with a delicate balance. Did you map the entire story out ahead of time? How difficult was it to maintain momentum and suspense for both stories?

Fiona Davis: I think if I’d had any idea how difficult it is to weave a story like that together, I would never have attempted it. However, I approached it the same way I would a piece of journalism, and mapped it out carefully. I spent a lot of time figuring out the characters of Darby and Rose – what their goals were, what fired them up and what intimidated them. Then I brainstormed scene ideas and wrote them on Post-Its – blue for Darby and pink for Rose. I stuck them up on the wall of my study and rearranged them so that they flowed from one to the other. From there, I wrote an outline and finally started on the first draft. I knew I couldn’t leave anything to chance. If I gave away a clue too early in one scene, it would ruin the tension of the mystery.

KS: Many people are familiar with the Barbizon from Sylvia Plath’s description in the Bell Jar, based on her time living there. What drew you to setting a larger story there? What type of research did you do to accurately capture the hotel in its heyday?

FD: I visited the building a few years ago, when I was looking for a new apartment, and toured a renovated condo unit as well as some of the public rooms. Having viewed old photos of the hotel online, the drastic changes surprised me. And when I learned that a dozen or so of the former hotel residents had been grandfathered in to rent-controlled apartments on the fourth floor, I wondered what they thought of the transformation and realized I had a story to write.

As a former journalist, I love research. The possibilities are endless, and it’s all about gathering as much information as you can. So I interviewed women who stayed at the hotel in the 1950s and 1960s to find out what it was like. One former guest described the Barbizon as a beehive of tiny rooms, and of course that image had to be included in the book. The specifics are what make or break any piece of writing, whether fiction or non-fiction, and hearing about the many rules of the Barbizon Hotel (and the ways the girls broke the rules) made the place feel real to me.

KS: In your book, you explain, in the 1950s, the Barbizon Hotel housed women on different floors, according to their professional aspirations, and this created a social hierarchy based on the women’s presumed ability to land a desirable husband. The models were at the top of this hierarchy, then the women who worked in women’s publishing, and finally, at the bottom, the women training to be secretaries. This social hierarchy seems archaic, yet it doesn’t seem like our culture has moved completely beyond it either. Rose, living in the Barbizon in 2016, is not immune from being judged by her looks, or subverting her own interests for a man she plans to marry. To what degree and in what ways do you think this hierarchy still exists for women?

FD: Back in the 1950s, women lacked economic power, so landing a man was the surest way to security. In fact, I remember asking one of the former guests in an interview how much a room at the hotel cost, and she replied that she had no idea, as her parents paid the bill. On top of that, women’s magazines in that era offered advice to the married girl along the lines of “Put lipstick on before you come downstairs in the morning.” Good looks garnered a husband which ensured safety. But even today, I see women who have been defined as wives and mothers, and then struggle to reconfigure their identity after divorce, or once the kids leave home. So I was eager to explore the themes of social hierarchy and marriage in the book as it existed back then and still does today.

KS: In 1952, Darby comes to New York knowing no one, and she is befriended by the hotel maid Esme. Esme sneaks Darby out of the hotel at night, and takes her to a jazz club. Other women at the Barbizon warn Darby to stay away from Esme, claiming she is trouble. Did the Barbizon women judge Esme, in part, because of her Puerto Rican ethnicity and her status as a maid? Were jazz clubs considered seedy venues at the time?

FD: The 1950s saw a huge influx in the number of Puerto Rican immigrants to New York City in what was known as the Great Migration, and they were met with hostility and discrimination. Because of that, Esme would never have made it through the front door of the hotel: guests of the Barbizon had to provide three references to be admitted, in part to ensure that they came from “good” families.

In the 1950s, there were a number of jazz clubs – like Birdland and the ones along 52nd Street – that were very popular with all kinds of people and not considered seedy at all. But as part of my research, I discovered a transcript by an informant, published in The New York Times in 1951, that described the jazz club/drug scene in harrowing detail, naming which musicians sold drugs, and in which clubs. My aim with the Flatted Fifth was to recreate one of the smaller, after-hours clubs where musicians would gather after their main gigs to play together and challenge each other musically, a place most Barbizon guests wouldn’t venture into.

KS: I was intrigued by the descriptions of Darby’s youthful appearance. For the most part, she considers herself plain, even unattractive. Later, others see her as beautiful. Unlike in a film, we can’t judge for ourselves so I didn’t feel like I quite knew how attractive she was. In your mind, was she unwittingly attractive, or plain but occasionally made beautiful by her personality?

FD: That’s a great observation. Darby definitely feels she’s uglier than she really is, but it’s more a reflection of that time period. As most women back then wouldn’t dream of leaving the house without lipstick and coiffed hair, the lack of attention Darby pays to her appearance means she’s plain in comparison. But with make-up on and a little backcombing (thanks to Esme), she can hold her own. My guess is that if she’d come of age in the 1970s, with its emphasis on a more natural look, she might have felt less dowdy and more confident.

KS: In 2016, Rose joins a media start-up which initially markets itself as an online New Yorker. But her boss pushes her to sensationalize her story about the 1950s Barbizon women, and eventually decides that long-form articles don’t attract enough views and their publication should instead focus on clickable visuals that will go viral. Do you think long-form journalism is an endangered art form? Has the cacophony of the Internet, particularly social media, shortened readers’ attention spans? As a novelist, do you feel any of this pressure, say to write stories that can be marketed with a snappy pitch?

FD: I went to journalism school in 2000, when digital media was just coming into its own, and the changes have been tremendous since then. I do worry about the lack of investigative journalism today, as newspapers cut back and shut down because the business model is no longer viable. In the past, reporters from smaller newspapers acted as the gatekeepers, attending school board meetings and town hearings where important decisions got made. If elected officials aren’t held accountable at the local level, it’s way too easy for corruption to take hold.

At the same time, the Internet offers a wider reach for stories that may have not otherwise been noticed, and instead go viral. And non-profit newsrooms like ProPublica are getting important stories out there. In terms of fiction, I think most books can be marketed with a snappy pitch – that just takes a good editor. But the book itself should be a luxurious deep-dive into another world, one you don’t want to escape from.

KS: In a conversation with her boss, Rose is annoyed when her boss refers to her story about the Barbizon women dismissively as “chick lit.” What is your take on the term chick lit, and, more broadly, the category of women’s fiction? I have read books of women’s fiction that, if they had been written by a man or been centered on a male character instead of a female one, would certainly have been labeled literary fiction. Does the women’s fiction label ever serve to diminish women writers, or do you think it communicates useful information?

FD: I was speaking with someone the other day about all the famous women who’d lived at the Barbizon Hotel, and we wondered that if it had been a men’s residence filled with Oscar- and Pulitzer Prize-winners, it would probably have a plaque outside celebrating that fact. Women have played second fiddle for so long, and I think it’s the same in the world of women’s fiction, where themes concerning domestic issues are considered non-literary. On the other hand, I find I am drawn to books written by women about women, so the women’s fiction label is useful for me in choosing what I’ll be reading next. I just don’t think they should be considered “less than” books written by men, about men. And the term “chick lit” is just annoying, and demeaning!

KS: When Rose is researching Darby’s story, she sees much of herself in Darby’s struggle to define herself while making a living, forming friendships and finding love as a single woman in Manhattan. One key difference between the two is Darby is in her late teens and Rose is in her mid-thirties when their (original) stories unfold. Is there a reason you made Rose so much older than Darby? Is there a social equivalence between those ages given cultural shifts and changes since the 1950s? What was the average age of the women living at the Barbizon Hotel in the 1950s?

FD: I would estimate from interviews that the average Barbizon resident in the 1950s was around nineteen. The average age of marriage for a woman back then was twenty, whereas today in New York City, the average bride is twenty-eight. I liked the idea of Rose skewing slightly older, having had time in the work force, and using the idea of marriage and partnership as a way to avoid dealing with the fall-out from her career. To me, that makes her slightly retro. On the other hand, young Darby is determined to never marry, which puts her ahead of her time. By making them both out of step with the times they live in, I hoped to be able to ramp up the inner and outer conflicts for Rose and Darby.

KS: What drew you to writing historical fiction and tying it to the present? Are there other books you would recommend that have adopted the same structure?

FD: I was drawn to writing dual-narrative historical fiction because I thought it would be the perfect way to represent the changes in the building and the city that residents like Darby experienced over many decades. Books I’d recommend include Geraldine Brook’s People of the Book, which covers a lot of ground, from the Inquisition to present day, and Kathleen Tessaro’s The Perfume Collector which has a similar alternate structure The Dollhouse does, but set in France and England. Both are powerful, lush books that transport you to another place and time.

Fiona Davis began her career in New York City as an actress, where she worked on Broadway, off-Broadway and in regional theater. After 10 years, she changed careers, working as an editor and writer and specializing in health, fitness, nutrition, dance and theater. She’s a graduate of the College of William and Mary and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and is based in in New York City. You can buy The Dollhouse here.