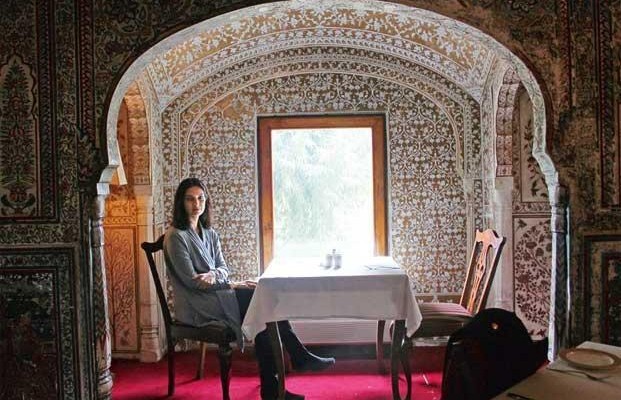

Author, Jhumpa Lahiri

Pulitzer prize winning novelist Jhumpa Lahiri, author of “Interpreter of Maladies,” “The Namesake,” “Unaccustomed Earth” and “The Lowland,” has written a linguistic memoir that chronicles her efforts to learn and write Italian.

In 2012, the author uprooted her family and moved them to Rome. There, she immersed herself in everything Italian. What initially began as rudimentary journal entries turned into an autobiographical work written in Italian that examines the process of learning to express herself in another language. The result? An exquisitely rendered account of the journey of a writer seeking a new voice.

At work in this collection of vignettes is a discerning and fastidious mind. Lahiri’s prose is like fine lace, carefully wrought and of the highest quality. But you wouldn’t know this if you read recent reviews. They were unfavorable at best, and in some instances, scathing—Dwight Garner of the The New York Times, for example, was so unimpressed that he dared to suggest that if Lahiri continued to write in the Italian language, she risked falling into literary oblivion. Clearly, Lahiri failed to meet some of her readers’ expectations. And, never has the saying “an expectation is a premeditated resentment” been more true that in the case of reviewers who didn’t get what they were expecting.

The expectation—a travelogue perhaps? Colorful and textured descriptions of the author’s favored haunts followed by recollection and thoughtful rumination? Some critics might have been surprised to find that the author’s fascination with the chronicling of the “process” was limited to reflection on vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. They felt that it was missing the color and clamor of Italian life. The Guardian’s Tessa Hardley, for example, wrote:

Lahiri’s book feels starved of actual experiences of Italy, or reflections on how that language gives form to its different world. Monkishly, all her contemplation is turned inwards on to her own processes of learning, not outwards on the messy imperfect matter the language works to express.

In retrospect, Lahiri’s book would have benefited from descriptions of more of what her daily life was like and its relationship to language learning. This however doesn’t mean that Italy served as a convenient backdrop for Lahiri’s language experiment. We may not have learned more about her daily walks to the market or exchanges with il postino but there is no question that the country and its language was her principal muse. The passion that Lahiri feels for her linguistic project is visceral. In the Chapter titled, Venice, Lahiri writes:

Walking in Venice, like writing in Italian, is an experience that throws me off balance. I have to give in. Writing, I come up against so many dead ends, so many tight corners to get myself out of. I have to abandon certain streets…there are moments in Italian, just as in Venice, when I feel suffocated, distraught. Then I turn and, when I least expect it, find myself in an isolated, silent, shining place.

As someone who enjoys the process of writing, creating and meaning making for its own sake, and not outcome, I appreciated Lahiri’s book as is. Her love for the language (and the country) makes you want to uproot your own family and immerse yourself in it with the same gusto that she does. More importantly, for the author, writing the memoir helped her find herself again. In interviews, Lahiri talks about how becoming famous altered her relationship to the writing process. All of her life, Lahiri answered to the expectation of others. She was expected to speak her mother tongue (Bengali) and her adopted one (English). She learned the English language as an immigrant in the US. Her knowledge of it quickly surpassed what she would ever learn in Bengali. Still, the English language has represented a consuming struggle for her. The English language, she writes “has represented a culture that had to be mastered, interpreted. English denotes a heavy, burdensome aspect of my past.”

The Italian language on the other hand wasn’t anything that was imposed on her. She chose it. Creatively, reading and writing in the Italian language meant that Lahiri could get back to the writing process and create art without any expectations. She writes, “I can join words together and work on sentences without ever being considered an expert. I’m bound to fail when I write in Italian, but, unlike my sense of failure in the past, this doesn’t torment or grieve me.”

Artists have turning points or milestones in their lives. For Lahiri, studying the Italian language was an act of rebirth. And while some critics worry about her taking up Italian permanently, most of us can’t wait to see where this rebirth takes her—in Italian, English or Bengali.

Other Books by Jhumpa Lahiri