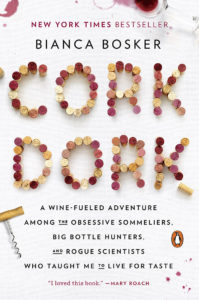

In a little over a year, Bianca Bosker transformed from a complete wine amateur to a certified sommelier. Cork Dork documents her journey through wine cellars, Michelin-starred restaurants, blind tastings, Bacchanalian parties, and scientists’ labs.

Filled with astute observations and written in a breezy, accessible style, Cork Dork provides a persuasive answer to the age-old question: why do people spend so much time, and money, on wine?

We’re delighted to talk with Bianca Bosker about her widely discussed and bestselling book, Cork Dork.

Kelly Sarabyn: Prior to researching this book, you had a full-time job as a tech journalist. Part of your motivation in delving into the world of wine was to get out from behind the computer screens and actually engage with the physical world. Interestingly, though, language and words turned out to be a crucial part of the experience of drinking wine. Can you explain the connection between developing a language to describe wine, and the experience of tasting and smelling it?

Bianca Bosker: When I left my job as tech editor to start the process of training as a sommelier, I had to learn to tune into this sense, smell, that I was not used to trusting. Learning to blind taste requires paying attention to this sense that bypasses our conscious brain. Part of the reason we think we’re bad smellers is we’re just not aware of all the smells we take in over the course of the day.

In order to internalize smells and hone our sense of smell, we have to attach meaning to odors, and that’s where the language comes into play. There is a sensory scientist at the University of California, Davis who is really the inventor of modern tasting notes. She developed a course that is required for all aspiring winemakers called the “Kindergarten of the Nose.” It helps people acquire an alphabet of smells, which is something we don’t do as children. You have to develop your smell memory, and expose yourself to different scents. On a practical level, that meant I would wake up in the morning, and describe all the smells I would encounter of the day. When I would shampoo my hair, I would try to put words on the aromas.

KS: I found it interesting that your experience drinking a glass of wine when you started the book and when you finished it were completely different. We don’t normally think of smelling or tasting as experiences that can be completely changed by acquiring a language around those experiences.

BB: Yes, and it’s a two-part process. One part is more physical. Our sensory organs are almost like muscles; if you expose yourself to different smells in a consistent way, you can improve your ability to pick up smaller concentrations of that odor, and tell it apart from others.

When I started, it was an open question whether I would be able to develop my senses. I had spoken with master perfumers and master sommeliers who suggested they had been born with this uncanny sensitivity. One gifted sommelier, for example, said when he was little his mother would hide cookies around their kitchen and he would find them by smell alone. And when I was the same age, when I was leaving for school, my mother would offer me a granola bar, and I would say, “No, thanks, I’ve got it,” because I knew that I had packed three dog bones in my pocket. From my perspective, dog bones were indistinguishable from granola bars. My sensory acuity was not high. I did not feel like I had a preternatural gift.

But what I discovered on my journey to become a sommelier is that any of us, with a little bit of effort, can improve our senses of taste and smell.

The second part of the process is more mental; it’s attaching meaning to information that we’ve never bothered to dissect and name. Research shows that in order to internalize and analyze information, we need to have the language to describe it. It is very difficult to recognize something if you don’t have a word for it.

As part of my effort to test whether I’d actually improved in this journey, I had my brain scanned by neuroscientists. We essentially recreated a landmark study that compared how sommeliers and amateur wine drinkers process flavors. And what that study found is that there was a signature pattern in the brains of people who had trained themselves to savor their senses. When the researchers fed wine to amateur drinkers, not much happened to their brains. They stayed relatively dark. When they fed wine to sommeliers, their brains were very active, particularly in the parts of the brain involved in higher processing, like memory, reasoning and critical thinking.

It’s a little bit of a spoiler, but by the end of my journey, I had actually acquired the brain of an expert. And what this research shows us is that if we don’t train our senses, information goes by us undetected. Whereas, if we hone our senses, that same stimuli turn into experience and knowledge. It can actually inform our worldview and enhance our understanding of the world. We can live more richly. And I think that is such an exciting takeaway because what starts with a glass of wine improves our lives far beyond it.

KS: That is a fascinating thing that came out of the book. Your wine mentor Morgan was very philosophical, and he thought that wine was transformative, and it could change his humanity, like a piece of art or music. What you are describing in expanding our ability to taste and smell could certainly be described as expanding our humanity, but did you come to feel like a single bottle of wine could be like a single piece of art and transform how you think?

BB: When I started this process the only thing I got out of a glass of wine was drunk. Now, though, a glass of wine affects me on a level that is not only physical but emotional and intellectual. I remember rolling my eyes at people who described wine as bottled poetry. And now I catch myself saying very similar things to my friends. So I think it is possible. Not every bottle of wine is going to nudge us into wondering about the world and our place in it. But I’ve certainly felt bottles that do that.

KS: Is that how it works on an intellectual level, that it makes you question your place in the world?

BB: I think so. On the emotional level, there are bottles of wine, that because they act on our sense of smell, which is our most intimate sense, they can move us to a very soulful place through their aromas. There are glasses of wine that I’ve stuck my nose into and they have transported me to my childhood in Oregon, or taken me back to summers with my husband on the beach in Massachusetts.

For the intellectual element, there are bottles of wine that embody a certain worldview. When you’re drinking these wines, you’re ingesting the winemaker’s way of seeing the world. There are certain natural wines, for example, that are made with the mindset of “nothing added, nothing removed.” They are attempting to connect the liquid in the bottle directly to the place that it came from. And those wines are curious in their own way; you’re drinking a thesis statement about how you capture nature through flavor.

One of the most incredible bottles I had the privilege of drinking in this journey was a bottle of Château d’Yquem. This wine—you’re not just drinking fermented grape juice, you’re drinking history. Château d’Yquem was one of Thomas Jefferson’s favorite wines. It was beloved by Russian czars. The winery is legendary for throwing out a year’s worth of work rather than making wine from what it considers subpar grapes. When I’m drinking that wine, it’s about participating in this larger historic and cultural enterprise.

Not every wine tells you an interesting story, though.

KS: I think that’s true of art, too, right? Not every piece of art is interesting. In the book, you were very respectful of different uses of wine.

BB: Regardless of whether I have paid $20 for a bottle of wine, or splurged on a $100 bottle, I’m going to come away from that bottle with a story. The story is, to me, part of the intellectual pleasure I get out of the wine. And that story could be about the international wine conglomerate that manufactured this wine to please as many drinkers as possible, or it could be a story about this radical French winemaker who said “To hell with the rules” and set off on his own journey to make offbeat wines. One of those stories is going to be more interesting, and one I want to come back to and reexamine over the course of several glasses. And one of them I am going to have gotten after the first sip. The intrigue and value of the story is going to change, just as it does among books. There are books that we read that entertain us on the beach, and there are books that we read for days that change how we think.

KS: Wine notes are often filled with descriptions that sound, to an amateur, farfetched. And you mentioned some studies that indicate they might be, at least in part. You tried to see if a bunch of sommeliers could blind smell chervil, for example, a smell often mentioned in wine descriptions, and they weren’t able to identify it. To what degree do you think wine descriptions (like chervil, or raspberries) are referring to a particular smell in some particular wines—a language specific to wine—and to what degree are they referring to the actual smell of the object in question (chervil or raspberries)?

BB: That’s a great question. The first thing I’d say is that what most amateur, and even professional, drinkers don’t realize is that the language of tasting notes is actually relatively new. It has become so ingrained in wine culture that we have lost sight of the fact that the tasting notes are only as traditional as disco. It came out of work done by sensory scientists who were looking for a more accurate and concrete way to talk about the aromas of wine. They came up with a few dozen different descriptors that described wine in terms of an animal, mineral or vegetable.

What’s happened in the several decades since is that this specific language has been turned into this flowery, unspecific romantic and evocative prose that sounds nice but doesn’t mean a whole lot to most drinkers. Tasting notes have generally become more about marketing than meaning. Rigorous, scientific language doesn’t get people excited about wine, nor does it make them want to spend a lot of money on wine.

I think, though, that there is a surprising logic to tasting notes in some cases. Just as an example, for a long time, people have described Sauvignon Blanc as smelling like green bell peppers. It turns out the Sauvignon Blanc grapes and green bell peppers both contain a class of chemicals known as pyrazines. So there is a scientific basis for that comparison.

That being said, if you look at how tasting notes have evolved over history, you can see how much they are a reflection not of the wine but of the people drinking it. In the early 20th century, for example, wine was described in terms of class differences. As people become fixated on health and wellness in the 1980s and the 1990s, wine was compared to a bounty of healthy fruits and vegetables. In the age of jazzercize, it was “svelte” or “muscular” or “lean.” Now, as we seek to quantify our lives in all regards, we are starting to use more scientific terms to talk about wine.

Ultimately, I came to appreciate the flowery tasting notes because they can be so wonderfully intriguing and evocative. Morgan, my wine mentor, would come up with these insane, off-the-wall ways of describing wines, and they would make me want to instantly stick my nose to whatever it was he was drinking. And sometimes they are more accurate in describing your own felt experience with wine. I think there’s a place for accuracy and a place for poetry. I’m just not confident the wine industry always knows when to be accurate and when to be poetic.

KS: In your book, you mention that 86% of Master Sommeliers are male, even though it’s been thirty years since females started joining their rank. Why do you think the profession, especially at the top levels, remains so heavily male?

BB: As with many fields, the wine world’s gender imbalance partially has its origins in history: the job of sommelier has traditionally been dominated by men. When Americans imported the idea of restaurants, which first emerged in France, they copied not only the pomp and circumstance of fine dining, but also the tradition of an all-male staff. Right now, there are arguably more women than ever before pursuing careers in wine. But they still have to grapple with issues and indignities that men do not, and it’s hard to see how some of these can’t be blamed for delaying the progress of women into the upper echelons of the industry. As I wrote in an essay for Refinery29, during my time training as a sommelier, I witnessed and experienced sexism of various forms. There was an auctioneer who informed me, along with a room full of our colleagues, that I’d provided him with hours of masturbation fodder. Another colleague who invited me to share his “big” hotel room. Male guests who willingly confused my politeness for flirtation, and female guests who doubted me in ways they didn’t my male colleagues. I came away with the impression that the female somms who step out on the floor each evening are often saddled with an extra burden that their male counterparts avoid: the men have to command authority, while the women have to command authority and suggest they’re open to being flirted with. This is exacerbated by the fact that it’s a tipped industry, where people pay you only as much as they like you.

KS: You write that economists determined that after $50 to $60 a bottle, the increasing cost of wine was not determined by any objective measure of quality. Price after that point was driven by more subjective factors, like cultural prestige and history. Studies show if we know a wine bottle costs more, we will experience it as tasting better. But to what degree are expensive wines just status symbols?

BB: Our impression of the flavor of wine is not only shaped by taste and smell, but also the price of the bottle, our expectation of it, the people we are drinking it with, the color of the room, the music that is playing. All of those things add up to our experience.

While trying to understand why collectors go crazy for certain bottles, I went to this sort of wine orgy for the mega rich, a celebration of the wines of Burgundy, and it turns out that one of the most notorious wine forgers was rumored to have passed off a lot of his fake bottles in this epicenter of knowledgeable collectors. And I think part of the reason that happened is that we are sometimes willing to suspend disbelief in the name of pleasure, and our expectations flavor the glass of wine.

That being said, I think one of the really incredible things about learning to blind test is teaching yourself to stay true to your own felt experience. I came out of this whole journey feeling like a lot of us settle for second-hand sensing. We let price and brands and fancy menu descriptions substitute for our own judgments of the food in front of us. What you have to do when you blind taste is get rid of all your preconceptions. Get rid of your personal biases. Really force yourself to analyze the feeling of the thing in front of you. That let me be more honest to my own felt experience of the world. Instead of feeling like I should hate American Cheese because everyone tells me it’s processed and isn’t really cheese, I rekindled my love for it. I realized I can explain to myself why this is delicious. I can analyze the mouth feel, the way it adds moistness to eggs and toast. And you know what, I like it.

My experience made me realize that by developing our sense of taste, we develop greater confidence in our taste in all things. The mindset that I bring to blind tasting is now the mindset I bring to the novels I read, and the movies I see, and the music I hear. It is important that we figure out a way to tune into our experiences in the face of all the things that are designed to play to our cognitive biases.

KS: On a more practical note, if a book club of wine amateurs was meeting to discuss your book, what wine would you recommend people bring?

BB: First, if any book clubs want to read Cork Dork and want wine suggestions to pair with it based on their personal taste, I’m happy to play sommelier and they are welcome to Tweet me or message me on Instagram. I’m always happy to play book club sommelier, or even Skype in.

The bonus is if you look at Cork Dork, it comes pre-wine stained. There are splotches of wine on the cover already. So no one will judge you. For wine, I would say a Riesling would be fun, and in case you’re thinking you don’t like sweet wines, there are many supremely excellent dry Rieslings. They tend not to be super high in alcohol, which means you can drink a lot without getting smashed. Rieslings also tend to have interesting complexities complemented by a refreshing zing of acid. That is a description that also might apply to Cork Dork. It’s been called subversive because it doesn’t stick to the wine world’s script.

Really, though, the best wine to drink with Cork Dork is a wine that you’ve never tried before. The book is all about encouraging readers to have an entirely new and different relationship to wine. It’s about reconfiguring your relationship to taste. So try the wine from the region you’ve never heard of, from the grape you can’t pronounce. Just live dangerously.

KS: I think that’s a good note to end on. Thank you for talking with us!

Bianca Bosker is an award-winning journalist who has written about food, wine, architecture, and technology for The New Yorker online, The Atlantic, T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Food & Wine, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, and The New Republic. The former executive tech editor of The Huffington Post, she is the author of the critically acclaimed book Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China. You can buy Cork Dork here.