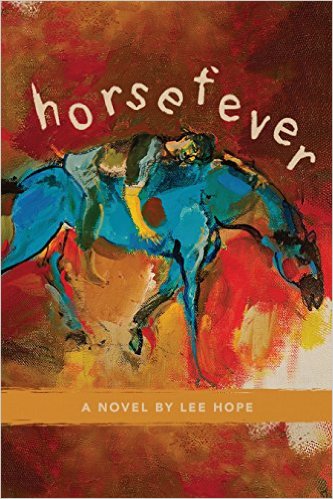

Inspired by an actual murder case, Horsefever is a masterful work of literary suspense. Equestrian Nikki Swensen and her fiery horse trainer Gabe often leave their “horse widowed” spouses behind to train and compete. As Nikki and Gabe’s passion for riding horses becomes more intense and reckless so do their spouses’ jealousies and fears.

We are delighted to discuss Horsefever with its author Lee Hope, the editor-in-chief of Solstice Literary Magazine.

Kelly Sarabyn: A significant part of Horsefever was about the relationship between humans and horses. Do you have a passion for horses? Do you think the level of intentionality Nikki attributed to her horses—Beau smirking, joking with her, rebelling, for example—was real, or was it her personifying and projecting?

Lee Hope: Yes, a level of the novel is about communication between humans and nonhumans, in this case horses. That is, how do we, through our feelings, gestures, thoughts, words and tones of voice relate to animals, and how do they see into us in a way that humans do not. Recently, an article in The New York Times Magazine reported on the empathy between injured vets and abused parrots. Each species has its own language, and horses have theirs, and if we are going to relate to a thousand pound beast, how do we learn their signs and signals and how do we teach them ours? In a sense, Nikki, one of my four protagonists, and Gabe, her horse trainer partially paralyzed in a riding accident, connect more effectively with horses than with humans, and that is part of the suspense in the novel. We see Nikki and her husband Cliff not able to understand each other, while she thinks she understands Beau, one of her horses. She is, to an extent, attuned to him. Yet, yes, she certainly also personifies this horse. And she definitely projects her feelings onto him, even on the first page of Horsefever when she says, “You’re the best, when you want to be, which isn’t often, but don’t be afraid. You’re just excited, like me, and we can’t help that. We’ve got the same temperament.” Which they don’t, because Beau is relatively calm and consistent, for a horse, while Nikki is hyper and mercurial.

And yes, I have a passion for horses, but I have even more of a passion for human beings, so the central focus of the book is on Nikki and her landowner husband, Cliff, and on Gabe, and his wife Carla, and their fraught, caring, contradictory marriages.

KS: When Nikki first met her horse trainer Gabe, they both agreed that they needed to eliminate Nikki’s guilt and fear in order for her to be a successful rider. I wasn’t sure what the connection between riding and feeling guilt was—is it that guilt would undermine her self-confidence and make her hesitant? Where was her guilt coming from? Do you agree an ideal rider would have no fear? It seems like a small amount of fear might keep a rider from making dangerous moves that could lead to disaster.

KS: When Nikki first met her horse trainer Gabe, they both agreed that they needed to eliminate Nikki’s guilt and fear in order for her to be a successful rider. I wasn’t sure what the connection between riding and feeling guilt was—is it that guilt would undermine her self-confidence and make her hesitant? Where was her guilt coming from? Do you agree an ideal rider would have no fear? It seems like a small amount of fear might keep a rider from making dangerous moves that could lead to disaster.

It seemed like Gabe believed as long as you were a fearless (and technically able) rider, you could control a horse—do you think that is true?

LH: Guilt is between humans because horses do not feel guilt. At least, I don’t think they do. Gabe’s emphasis with horse training is on Nikki confronting her fears. “Fear is contagious,” Gabe says. Why is her fear dangerous? Because her fear can trigger the horse’s innate fear. Fear is a survival instinct. Horses have survived since prehistoric times by fear. They are creatures of prey. They are tuned into the fear of those around them in a heightened sense. In an instant they can bolt, rear, buck you off, break your leg, collarbone, neck. After a concussion I had from a mare bucking me off, one doctor said that there are more head injuries in horseback riding than in motorcycle riding. That is partly because you cannot totally control a horse. No matter how much we love this animal, and train it, it can still maim us, or kill us, particularly if we are riding across the countryside and taking jumps as Nikki is in the sport of eventing. The horse is free, to an extent, outside of the ring, the horse is in nature again. So no, Gabe does not expect her or any rider to be thoroughly fearless. He wants her to be in control of her fears, although he knows total control is a myth.

KS: The book rotated perspectives among four different characters: Nikki and Cliff, who are married to each other, and Gabe and Carla, who are married to each other. But many of Cliff and Carla’s chapters seemed to focus more on the travails of Nikki and Gabe than on Cliff or Carla independently. At the end of the book, I felt like I knew Nikki and Gabe better than Cliff and Carla, especially Cliff, who remained the most mysterious to me. Was that intended? Was this more the story of Nikki and Gabe, or do you think this discrepancy was more a function of their personalities within their marriages—namely, Nikki and Gabe were very intense, passionate people who set the tone and script for those in their orbit.

LH: This question is my favorite so far partly because it shows how different readers can respond differently to different characters. In fact, this question could bring us back to Reader Response Theory, which stated that the reader co-creates the character, that the book itself does not exist until the reader opens it.

So I’ll say my response is that my personal favorite character is Cliff especially because he is mysterious, and yes, his mystery is intended. Why is it that some of us hold in our emotions, to our own detriment? What constitutes repression, denial? What are the consequences?

Cliff feels deeply, is passionate about his wife, yet he cannot bring himself to utter his feelings, as in one scene, during their slow dance when she catches a glimpse of his face in the mirror and suddenly sees the tenderness, his love. But then they step turn away from the mirror, and he is again hidden from her, as he is hidden from himself. He is, in my view, a compassionate but tragic character.

And, yes, Nikki and Gabe speak similar emotional languages, and in a sense this novel is about emotional language, as that between horse and rider. But Nikki and Gabe for all their intensity also do not totally connect. She does not see the darkness in Gabe’s meditation. He does not see her love for Cliff.

And yes, it is the connection that Nikki and Gabe share with horses that propels that action, and their obsession with winning, and the impact that obsession has on their spouses. Yet both Cliff and Carla fight back. They even conspire together to keep their mates. It is the clash of obsessions and ambitions that drive these two couples toward violence.

We should try to choose our obsessions carefully. If we even have that choice.

KS: At one point, Gabe says that by training Nikki to be a better rider he is “turning [Nikki] into someone else.” What’s your take on this statement—do you think it is plausible, or is Gabe overestimating his own power, and the power of becoming a better rider? Is that enough to transform a person?

LH: Gabe wishes to believe he is transforming her. He wants this power, this control. He is partially paralyzed and can never compete again, so he is living vicariously through her. So yes, he is overestimating his own power because Nikki lives also apart from horses and competing them, partly in her love for Cliff.

On the other hand, we often think of sports inculcating character, of discipline making us better people, of the mind/body connection’s transformative power. So Gabe is not totally misguided to believe that through a sport, especially a life-threatening one, he could have power over her.

KS: A major theme in the book is Cliff’s resentment that Nikki is—in his perception—risking her life for insufficient reward by riding horses (as he says, “each eventer a potential victim lurching toward premature death.”) Cliff played competitive football when he is younger so he thinks he can understand the pleasure Nikki gets from riding, but he still thinks that this pleasure isn’t enough to justify the risk. In your mind, was Cliff being rational in his feelings? Is riding really that dangerous?

LH: Yes. Riding is as dangerous as competitive football. I do not know the statistics of how many football players are paralyzed or killed in action, but I do know that many eventers have suffered injuries, including concussions, and death. For instance, the tragic accident of Christopher Reeves, “Superman.” His horse was taking a jump, and partly because he was such a large man, he leaned forward midair, the horse was thrown off balance, and Reeves flew over the horse’s head, landed on his neck and was paralyzed. So Cliff was rational in his assessment of the danger of eventing. Yet at the same time he valued it, even identified with the risk, the high, the joy of defying death.

KS: Do you think Nikki was being selfish in continuing to ride given Cliff’s feelings? Was Cliff being selfish in asking her to quit? Indeed, would Cliff have loved her as much if she wasn’t someone who loved the thrill of riding?

LH: Some of us can be attracted to the very traits in another that we also rebel against. Another reason love relationships and marriage fascinate me. Their irrationality. I think both Nikki and Cliff were self-motivated, meaning that they had other needs than their love for each other. Nikki put her riding before her husband. Cliff knew riding was her passion yet he wanted her to stop. Yet Cliff loved her more for taking risks. He was a risk-taker himself, in sports and in business, and in his choice of Nikki as a second wife. Taking risks is a language they share. Living on the edge, even while they both crave security in marriage and family. Another contradiction.

KS: Cliff is portrayed as steady, quiet and reserved. He claims “saying nothing has got him far in life.” While he certainly succeeded professionally, he didn’t seem particularly happy to me and so I’m not sure I would agree with his assessment that his emotional reserve served him well. Do you have a different take? Do you think Cliff was his happiest keeping to himself?

LH: I partially answered this question above when I talked about Cliff as my favorite character, but I’d like to add that he cannot really help his reserve, even when his wife tries to draw him out. His father was Cliff’s role model as a man. His father held his feelings in, believed there was a dignity to that. Cliff realizes his withdrawing can be counterproductive, even destructive, yet he cannot stop withholding his feelings, even while he is capable of a deep love. Many men could identify with this predicament.

KS: Did you think the nature of second and perhaps last chances played a large part in the book? This was Nikki’s second chance at riding horses, Gabe’s second chance at working with horses, and Cliff’s second marriage. It seemed like this idea—that this was their second, and perhaps last, chance to do these things well—lent a certain desperate determination to everyone’s actions that ultimately drove the trajectory of the novel.

LH: One of the most compelling aspects of the actual murder case was that the characters were nearing middle age. They were in that in-between phase, more volatile perhaps than adolescence, when renewal seems possible if one can take a chance. In the actual case, and in the novel, all four feel time closing in, even Carla, Gabe’s wife. She feels she has nursed Gabe through his recuperation from his riding accident, and now they have another chance at happiness. Her desperate attempt to secure his loyalty plays a major role in the violence at the end.

Also, personally, I am a big believer in second chances. I believe people can change and grow and find new paths to express themselves. I believe in reformation in prisons, for instance, to help people on probation to start new lives. In fact, I teach men on probation in a program called Changing Lives Through Literature, and I have seen some of them go on to grasp a second chance and find a better life. I believe some people can find new love in second marriages, in new faiths, new careers, new places. It’s not only an American belief that we can rediscover ourselves, but it’s certainly a prevalent part of our cultural history.

KS: A couple times characters equated horses to a religion. By Gabe, in earnestness, and by Nikki’s daughter, in jest. Do you think it is common for horse people to feel that strongly about horses? Do you think Gabe sees horses as a religion partly because the rest of his life is so anemic? Other than Carla and horses, he doesn’t seem to have any other interests or friends. Do you think the fact that half his body was left limp by a horse riding accident prevented him from starting his life over, with new interests?

LH: There is a saying that horseback riding is not just a sport, it’s a way of life. The thrill of riding; the caring for a powerful but vulnerable animal; the relationship with nature—the awareness of weather, the consistency of soil, of sand or turf, of open space; and the connections with other horse people who feel the high of all of these duties and privileges, make horsemanship a way of life.

And counter to common lore, many horse people don’t have much money. There are certainly class differences at the top competitive levels, no denying it, and that theme also runs throughout the book. The owners and the riders are separated often by a financial and class divide. But some who are devoted to horses can find ways to enter into the world of eventing, as Nikki did by buying racehorses cheap off the track and retraining them. Even some horses get a second chance.

And yes, horses were a religion to Gabe. Horses were his meaning in life, and as some of us who have been maimed, physically or emotionally, he was even more obsessed with rediscovering the vitality, the force, that he found by living through them, and living through Nikki.

Yet horses are not a path to God, as Gabe and Nikki find out.

KS: For me, there were ambiguities in how far Cliff was willing to go to stop Nikki from riding. It was unclear whether he was willing to harm her or not. Did you intend for that to be open to interpretation, even from Nikki’s perspective?

LH: Here I don’t want to give too much away when it comes to Nikki’s response. I will say that any threat from Cliff is intentionally ambiguous. Readers will interpret it according to their lights.

KS: Have you read Life Drawing by Robin Black? The tensions in the marriage portrayed in that book—a husband’s jealousy of his wife’s artistic passion, a relatively isolated marriage encountering outsiders—reminded me of your book. Is there a particular literary tradition you would place Horsefever in?

LH: Even in graduate school, I had a deep interest in literary suspense, such novels as Before and After by Rosellen Brown, Affliction by Russell Banks, The Secret History by Donna Tartt, all focused on character-driven events that lead inevitably to violence. I could mention also Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, and such genre-bending writers as Raymond Chandler and James Lee Burke. Even in some of my published stories I’ve written about crime and injustice.

KS: There’s a great deal of tension in this book—tension in Nikki and Cliff’s marriage, tension in the danger of horse riding, tension between Nikki and her horse trainer Gabe. When you were writing, did you already know the ending, or did that unfold as you wrote? I don’t want to give anything away, but the ending is very dark—did you ever entertain a lighter ending, or did it seem inevitable these characters were headed toward some kind of a catastrophe?

LH: This novel is inspired by an actual murder case that fascinated me because of the tensions between two married couples. If these two marriages had not intertwined, if jealousies had not grown and erupted, all would have proceeded within boundaries. But the relationships take their own course, like a horse given its head.

I also don’t want to give away the ending other than to say we see some characters meet sad fates, while others might be seen to be given a second chance. One reader, a horsewoman, said that she found the ending uplifting. As mentioned, this could be considered a novel of second chances. May we all be given such opportunities and the courage to commit to them fully.