The following is a guest post by author A.M. Linden. Enjoy!

At its simplest, a frame narrative is a story within a story. From there the possibilities are, if not endless, something close to it. What most frame narratives have in common is the narrator of the outermost frame story directly addresses a present-day audience and the events of the inner, framed story take place in the past.

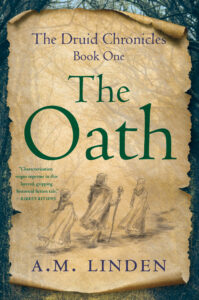

In keeping with this tradition, the first book of the Druid Chronicles opens with an omnificent narrator—by implication a contemporary historian—stating, “The events that took place in and around the Kingdom of Derthwald during the spring and summer of 788 AD have, understandably, been overlooked by scholars concerned with early medieval history. Even at its peak, Derthwald was never more than a minor monarchy, rising and falling within the span of forty years and leaving only a single, obscure reference to its existence in surviving documents of the period—besides which, most of those involved had good reasons for keeping silent.” Use of this frame serves the purpose of establishing the main narrative’s time and place, justifies the fact that the kingdom of Derthwald would not be found in the actual historical record, and hopefully arouses the reader’s curiosity about what it was that the characters needed to keep silent.

With the shift to the year 788 A.D. established, the main narrative becomes the “present” frame from which the narrator will, now and again, take the reader further back in time, as happens when a character whose villainy is the subject of four subsequent chapters is introduced as he appears “now,” by the omnificent narrator who makes the time change saying, “Despite the scathing comments about him being bandied back and forth in the tavern, Barnard was a mild and inoffensive-looking man. His habit of cocking his head to the left to compensate for his blind side gave him a perpetually quizzical look, more in keeping with the eager-to-please servant he’d once been than the cruel, tight-fisted miser he’d become,” then goes on to describe the events that led to the character’s transformation from an obliging servant to a cruel villain. As in the book’s opening segment, this recounting of the earlier events in Barnard’s life is intended to add to the reader’s knowledge of the pivotal events that set the central story in motion, as well as peaking the reader’s interest in a less-than-likeable character.

With the shift to the year 788 A.D. established, the main narrative becomes the “present” frame from which the narrator will, now and again, take the reader further back in time, as happens when a character whose villainy is the subject of four subsequent chapters is introduced as he appears “now,” by the omnificent narrator who makes the time change saying, “Despite the scathing comments about him being bandied back and forth in the tavern, Barnard was a mild and inoffensive-looking man. His habit of cocking his head to the left to compensate for his blind side gave him a perpetually quizzical look, more in keeping with the eager-to-please servant he’d once been than the cruel, tight-fisted miser he’d become,” then goes on to describe the events that led to the character’s transformation from an obliging servant to a cruel villain. As in the book’s opening segment, this recounting of the earlier events in Barnard’s life is intended to add to the reader’s knowledge of the pivotal events that set the central story in motion, as well as peaking the reader’s interest in a less-than-likeable character.

A third use of framing occurs later in the book, and is an example of a nested narrative, starting with the narrator’s account that “As the disciple of their shrine’s chief bard, Caelym had spent his formative years memorizing the hundreds of interconnected stories, songs, and odes that, taken together, comprised the nine major sagas that lay at the heart of the belief system of the followers of the Great Mother Goddess.” Next, the viewpoint shifts to the protagonist, with Caelym “. . .looking down at the expectant faces of his two sons, their eyes sparkling in the light of the campfire,” and shift again as he tells the actual framed story of a talking horse’s confrontation with an arrogant sprite—a fable with a moral which, not by happenstance, is one of the underlying themes of the series. While in the previous examples, it is the outer story that provides context to the inner one, in this case the choice of this particular story from several that are told throughout the series, was intended to reinforce the thrust of the larger narrative.

While the use of the frame narrative is in no way limited to works of historical fiction, it seems to me to have a special place in our genre, and it’s my hope that I did it justice in my story about Druid story-tellers. Additional information about the series is available on the website: www.druidchronicles788ad.com

A.M. Linden was born in Seattle, Washington, but grew up on the East Coast before returning to the Pacific Northwest as a young adult. She has undergraduate degrees in anthropology and in nursing and a master’s degree as a nurse practitioner. After working in a variety of acute care and community health settings, she took a position in a program for children with special health care needs where her responsibilities included writing clinical reports, parent educational materials, provider newsletters, grant submissions and other program related materials. The Oath began as a somewhat whimsical decision to write something for fun and ended up becoming a lengthy journey that involved Linden taking adult education creative writing courses, researching early British history, and traveling to England, Scotland, and Wales. Retired from nursing, she lives with her husband, dogs, and cat.