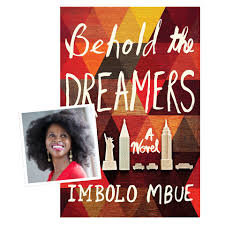

Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers is easily one of my favorite debut novels of 2016. In this story, Mbue gives us a glimpse into what it means to pursue the American dream through the eyes of two families: the Jongas and the Edwards. You have Jende Jonga, an immigrant from Cameroon, his wife, Neni, who is studying to be a pharmacist, and their young son Liomi. Their lives change, for the better, when Jende’s cousin helps him land a job with Clark Edwards, an executive at Lehman Brothers. The fates of the Jongas and the Edwardses become intertwined, but what you get is a carefully crafted story of the American Dream in crisis.Book Club Babble is happy to interview Imbolo Mbue and talk about her debut novel, Behold the Dreamers.

Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers is easily one of my favorite debut novels of 2016. In this story, Mbue gives us a glimpse into what it means to pursue the American dream through the eyes of two families: the Jongas and the Edwards. You have Jende Jonga, an immigrant from Cameroon, his wife, Neni, who is studying to be a pharmacist, and their young son Liomi. Their lives change, for the better, when Jende’s cousin helps him land a job with Clark Edwards, an executive at Lehman Brothers. The fates of the Jongas and the Edwardses become intertwined, but what you get is a carefully crafted story of the American Dream in crisis.Book Club Babble is happy to interview Imbolo Mbue and talk about her debut novel, Behold the Dreamers.

Maribel Garcia: Imbolo, thank you so much for taking time to be with us today.

Imbolo Mbue: Thank you so much for this opportunity, Maribel, and for your very kind words about the book!

MG: Let me begin by saying you hooked me with your first sentence. The line, in all caps, reads:

MG: Let me begin by saying you hooked me with your first sentence. The line, in all caps, reads:

HE’D NEVER BEEN ASKED TO WEAR A SUIT TO A JOB INTERVIEW.

Your readers soon learn that this plainspoken man, only recently mentored by a volunteer career counselor in the US was once a responsible farmer in West Africa and is now preparing for a very important job interview. In order to stay in the country and support his young family, his life now depends on how this interview will go. You beautifully create the stakes for Jende and show us what your protagonist longs for: economic security and well-being through a good job, a decent income, some savings in the bank, and a comfortable home. You managed to effortlessly inhabit the minds of characters who are new to America and its odd ways, but simultaneously show them as the new Americans that they are.

How did you come up with these two characters? Did real people inspire them?

How did you come up with these two characters? Did real people inspire them?

Imbolo Mbue: Yes, they were inspired by real people. Jende was inspired by chauffeurs I’d seen waiting in front of a building in Midtown Manhattan when I went for a walk one day. I’d actually walked in front of that particular building (the Time Warner Building) hundreds of times but on that day in the spring of 2011, I paused to think about what the chauffeur’s relationships might be like with the executives they drove. Being that I had lost my job in the recession, I was also curious about how the recession had affected the lives of other people, in this case the chauffeur and the executive and their respective families—that is how their wives and children came into the picture. Jende’s wife, Neni, was inspired by women I’d known while growing up, and also working-class women I’d known in America, women who were tough and determined and did what they had to do for their families.

MG: There is a quote by L.M. Montgomery that goes: “Isn’t it nice to think that tomorrow is a new day with no mistakes in it yet?”

For Jende and Neni, this is the appeal of America. A clean slate. They are in a new house, new country, new job and in new schools. In these moments, when we begin anew, we are naturally motivated to work harder. And we see Jende and Neni doing just that. Heck, if you wanted to ask if these two were “assimilating,” you could definitely say they were meeting some of that criteria. Jende and Neni not only take pride in their newfound American identity, but they also believe in America’s liberal democratic and egalitarian principles. And if you wanted to talk Protestant work ethic, well there is no one more self-reliant, hardworking and morally upright than this couple. This couple works hard and one of the biggest myths in our society is to believe that anyone who works hard will get ahead. Yet, any comparative statistic of socio-economic indicators shows that structural inequality is the reality. Did you initially intend to address the myth of meritocracy or did the story unfold organically?

Imbolo Mbue: When I began writing this story I had no idea which direction it would go. The story unfolded very organically and it was through writing and rewriting that I learned a lot about the characters. My main goal was to tell the stories of these two very different families, their hopes and their struggles. Clark and Cindy’s story is a story of a family in agony, and Jende and Neni’s story is one of dreams meeting with reality. Jende and Neni came to America with high hopes, and like you said, they work hard. But is hard work enough? For millions who are working-class, or people of color, or people who are socio-economically disadvantaged in one way or another, hard work might not be enough and that is a harsh reality to live with.

MG: There’s a very simple formula for creating the stakes (and thus suspense) in a story. You show the readers what your characters want and then you threaten it. And your secret weapon in Behold the Dreamers is the 2008 economic crisis. There have been many attempts to analyze the full cost of the financial crisis. Analysts talk about the GDP, unemployment rates, government bailouts, and lost household wealth. What’s more difficult to write about is the human suffering. How do you put a dollar value on human suffering? Most people can’t, but your novel manages to capture the emotional lives of human beings and to portray those lives and specific moments within the context of the maelstrom of the 2008 economic crisis. Does the human cost of economic breakdowns interest you?

Imbolo Mbue: I’m very interested in the stories behind numbers, especially at a time like the financial crisis when there were lots of dismal statistics. I remember in the heat of the crisis, sometimes when I heard of a company laying off X number of employees, I wondered who the employees were, and how long they’d been at the company and how that job loss would affect their lives. I’d lost my job at the end of 2009 and I was struggling to find a new job when I began writing this story, so mine was one of thousands of stories of how tough it was to be unemployed during the crisis. The crisis affected the two families in my novel in different ways, but ultimately, they both had to deal with it opening and widening up existing cracks. It was a tense time for many people—marriages were tested and careers were tested and dreams were tested, and sometimes reassessed.

MG: Raising the stakes, whether they arise from internal forces or from external ones, makes your protagonist’s character interesting and his/her stories memorable. That thrilling sense of momentum comes from the sense that the danger to their world keeps getting bigger. Some authors, unfortunately, raise the stakes and manage to sacrifice their characters. Yet, Behold the Dreamers is filled with fully-fledged three-dimensional characters that actually get stronger and more believable. You see this with the Edwards who are part of the 1%, but you made them human. The reader can still sympathize with them for various reasons.

Rarely do novelists portray the very wealthy with empathy, yet, you did. You could have made the Edwards a little more like Tom and Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby–either caricatured or overtly demonized.Was this your understanding from the beginning, or did you develop empathy with your characters as you wrote?

Imbolo Mbue: Oh, it was a long journey for me to develop empathy for Clark and Cindy Edwards. I wish I could say that from the moment I met them, I understood them and valued them and felt for them, but that would not be the truth. Writing this novel was a lesson in empathy, because in the beginning, I had so much judgment towards the Clarks and Cindys of the world. But to tell this story, honestly and completely, I had to learn to see them as humans—flawed humans, yes, but still humans deserving of empathy because they want many things the rest of us want. Developing empathy for Jende and Neni wasn’t difficult—they’re from my town, they’re immigrants like me, they’re black like me, but someone like Cindy Edwards, on the surface she couldn’t be any more different from me. I had to learn that showing empathy shouldn’t really have anything to do with having similar demographics or backgrounds or lifestyles. It’s about a shared humanity.

MG: Your novel definitely showed the disconnect between struggling immigrants and those who are born in the US with economic privilege, but it was very clear that the values and sentiments of the immigrants you portray mirror those of native-born Americans.Was this intentional?

Imbolo Mbue: Not at all. I’m amazed at how all this happened unintentionally because I didn’t ever sit down to write with any sort of agenda except to tell the story. It’s very interesting for me to now hear readers seeing all these similarities and dissimilarities and symbolisms, and I love to hear it, because I’m so close to the story that it’s hard for me to see all this for myself. And to your point, yes, I think that Jende and Neni Jonga do share similar sentiments to Clark and Cindy Edwards because they all have dreams of success and happiness for themselves and their children, and they each recognize the importance of family in their own ways, and they make choices—both good and bad choices—in the hope that it will help them and their families. But there’s also a huge disconnect, because the working-class Jongas don’t have the same advantages that the wealthy Edwardes have, and they’re from two very different cultures. This disconnect can be seen in the case of Vince Edwards, the older son of the Edwardses, who rejects the kind of opportunity many immigrants could only dream of.

MG: The goal of significant wealth has long been a part of the rags to riches story. Mrs. Edwards, for example, summers in the Hamptons, wears designer clothes and lunches with the right people. We later learn that she comes from a poor background and she feels vulnerable, her position always precarious. When Neni is her maid for the summer, you contrast both of their lifestyles and you see Mrs. Edwards holding on to one vision of the American Dream, while Neni holds on to hers. Mrs. Edwards has financial stability and does not fear deportation. She has everything that the Jongas want but is far from happy.

Behold the Dreamers is a tale of class divide, but it’s also about the good ole pursuit of happiness—that fundamental right mentioned in the Declaration of Independence to freely pursue joy and live life in a way that makes you happy (as long as you don’t do anything illegal or violate the rights of others). Questions about what makes us happy have long dominated the self-help industry, the expanding field of positive psychology and cultural conversation. Was the pursuit of happiness a theme that you purposefully set out to pursue in this novel?

Imbolo Mbue: Not the pursuit of happiness per se, but dreams, and the way the financial crisis affected the dreams of the characters. I was also interested in the price the characters had to pay to see their dream come true (in the case of the Jongas) and what they needed to do to hold onto their dream lives (in the case of the Edwardses). The dream at the center of the story ended up being the American Dream, which various characters in the novel embrace or wrestle with in their unique ways. There are characters for whom the American Dream has come true, and there are those who are still thousands of miles from achieving the dream. If a reader finds the pursuit of happiness as a theme in the novel, I imagine it is because happiness is at the center of the American Dream and the characters hope that attaining, or holding unto their version of the American Dream, will make them happy.

MG: Your characters were so rich in detail and so humane that I was filled with an almost frustrated kind of urgency, I wanted them to make it in America. I was hoping hard, cheering for their success. I will not spoil the ending for our readers by asking anything too specific, but I do have a question for you as an author: What does the American Dream mean to you? Do you think that people start to think about what it is that makes them happy when the combination of unprecedented prosperity and uncertainty about the future are the driving factors?

Imbolo Mbue: I’m not sure what the American Dream means to me because I’m very conflicted on the whole idea. I started writing this novel because I’d lost my job, and because I knew many people like myself who were struggling to get good jobs in the recession, and I knew people who worked hard but were struggling to get out of poverty because there’s a vast inequality in the distribution of income and wealth in this country and that puts millions at a disadvantage. So, I don’t believe this American Dream is accessible to everyone, in which case, I think we need to redefine the whole concept.

MG: And, lastly, have you started anything new and can you tell us anything about it?

Imbolo Mbue: I’ve been writing a few essays lately. I recently wrote an essay about voting for the first time in my life, which will happen this November— something I’m very much looking forward to. I also wrote an essay about what Christmas is like in my hometown of Limbe, Cameroon. Writing essays is very different from writing fiction, but I’m enjoying it.

MG: Imbolo, thanks again for joining us at Book Club Babble. Your novel has inspired change and makes us all think of what matters most. We are looking forward to your next novel.

Imbolo Mbue: Thank you, Maribel.