This month Book Club Babble is proud to feature a review/interview by guest blogger Sala Wyman.

This month Book Club Babble is proud to feature a review/interview by guest blogger Sala Wyman.

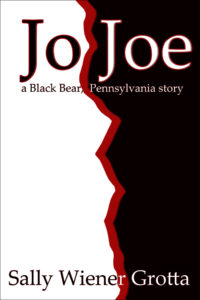

Jo Joe by Sally Wiener Grotta

Set in a fictional village in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania, Sally Wiener Grotta takes on the inner shards of racism with her novel Jo Joe, a Black Bear, Pennsylvania Story.

There are always a couple of ways to deal with the topic of racism and its effects on the victims. One is to just document the facts about oppressors and victims. Another is to take a higher road: the healing of victims, families, and communities. Ms. Grotta beautifully and skillfully takes the high road.

As a black American, I often read stories about people of color with a critical eye, with the unfortunate expectation that characters of color will show up in two dimensional caricatures or worse. I am delighted that Ms. Grotta, a marvelous storyteller, cleverly avoided that abyss. Once I picked the book up, I did not put it down.

The story of Judith Ormand, a biracial woman of Jewish and Black heritage whose teenage years in a fictional village in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania were filled with brutal racism, is one that explores healing from the trauma of bigotry with immense skill, empathy, and flawless emotional intuition.

It’s that emotional intuition that hooked me. I understand Judith’s rage. My own racial history left me with the same vow to never return to the Southeastern states that I visited so often as a child and teenager. But there is healing aplenty for everyone in this book.

Judith, the Jo in Jo Joe, returns to Black Bear, a place she vowed to abandon forever, for the funeral of the white Christian grandmother who helped raise her. Filled with rage and resentment for the community that humiliated and despised her as a teenager, she must also come to terms with being abandoned by the young white boy (Joe) with whom she’d fallen in love in high school.

The village has changed over time. There are the religious blends, the Moravians and the local Jewish community; the pastor, the Rabbi, and new Jewish residents who’ve come to the village since she left. As a teenager, Judith was the only non-white child in the village. Now a grown woman living in Paris, Judith is unable to see the change. Her every decision is motivated by rage and the memories of racism, memories that keep her relationships with people at an icy distance—until she once again faces the Neo-Nazi bullies who tormented her in high school.

As she struggles to reconcile her grandmother’s business affairs in the short week she has allowed herself for the visit, family secrets are revealed and community resentments exposed. Mrs. Grotta possesses the talent to shine a light on the inner landscape that leads to all of our healing, forgiveness, and redemption.

Readers can find more information about Sally and connect with her at her website: www.Grotta.net.

Sala Wyman: Why Judith? Writing about racism is complex enough, what is it about this particular racial conflict that drew you to her story?

Sally Grotta: When I write, I don’t typically start out with an idea for a tale or a theme that I want to tackle. Every story starts with a person who is born in my subconscious and starts nagging at me. That person is born already well defined, with a personality and problem and, usually, a name. So, on one level, I didn’t *choose* this particular racial conflict. I could be a bit contrary and say that it chose me.

However, certain types of issues haunt me and inspire my writing. I’m often confounded by the world around us. I don’t understand war or hate or prejudice. Violence and emotional destruction twist me up inside. So I write to try to comprehend what, to me, is unfathomable. I create characters I care deeply about and then put them into terrible situations to see if we can work out possible reasons, potential solutions together. Or if that isn’t possible (as it often isn’t, because the problems are so globally huge), then I hope to tweeze out some threads of understanding. That collaboration with my characters carries over into the form my stories take. For, to me, the most important things in life are relationship-based. So it is also in my creative life.

Why this specific kind of racial/tribal conflict? Because it is so human and common, and because it is multi-dimensional and therefore both interesting in terms of a story and quite realistic. Prejudice is a two-way street: I distrust you because you distrust me because I distrust you. An irrational downward spiral that is easier to ride than to try to break. In another novel “The Winter Boy” I used the metaphor of a snake biting its own tail to describe anger, but it applies to hate and prejudice, too. “When the snake feels the bite, it reacts by biting its tail more, which makes it even more painful, so he’ll bite even harder, and so on. It continues round and round, until it dies. If the snake could learn not to bite in reaction, it could break the cycle and live. But the snake doesn’t even recognize that he’s the source of his own problems. Instead, it reacts instinctively, in anger and pain.”

Once we see hate and prejudice in terms of that kind of two-way downward spiral, I feel that we can come closer to trying to break the cycles, to see each other as individuals rather than symbols, as people like us rather than as the frightening unknown or unknowable.

Having said all that, none of this is conscious when I’m writing. All that’s important at that time is the story that I’m compelled to write. First comes the character, with a problem (though it may not be the true core problem, but what she/he perceives as one). Then, the basics – the setting and other characters – become real to me, which establishes the story’s beginning. Almost as quickly, I usually know the first sentence or even paragraph, as well as the ending of the story. After that, it can take me years to unearth the full story, to fill the spaces between that first sentence and the end. As I write, I put my whole self into the story. So, it’s natural that issues that are close to my heart will become part of the story.

SW: You appear to have a level of comfort with several cultures—French, Jewish, and Black—and you dig deep into the heart and soul of what it feels like to be an outsider. Where did you get your multi-cultural knowledge?

SG: It started quite young, but was then nurtured by wonderful teachers and mentors, and some remarkable life experiences.

What artistic child doesn’t feel like an outsider at one point or another? I’ve discovered that many creative adults have sinew-deep childhood memories of not belonging, being different or somehow always being on the “wrong” side of lines that are drawn by social groups. I guess it’s because we saw or felt the world around us more acutely than our peers. Or maybe we hid those feelings less skillfully. Or is it possible that all children have those feelings but some of us experience a type of transference that softens rather than hardens us. I’m not sure why some children lash out as bullies and others, once hurt, become more empathetic to pain or injustice beyond what they experience within their own skin. Wouldn’t the world be a far better place if more adults carried those lessons with them into the greater world? For me, it certainly helped to predispose me to be open to cultural vistas beyond my childhood backyard.

Over the years, I was fortunate to have been influenced by family and friends, teachers and other mentors who, through discussions, books shared and ideas debated, widened my perspectives. I learned history, philosophy, world cultures and religions not only as great storytelling, but as points of reference and guideposts. Between my Jewish upbringing and my Quaker education, both of which included learning about and discussing others’ cultures and religions, I was exposed to a way of thinking that assumed the more you learned the more questions you would have. Answers are often temporary stop gaps until you realize that a wider spectrum of questions is always just around the corner. That’s part of the adventure that my education prepared me to appreciate. Each morning offers another path to explore, new people to try to understand. Such understanding rests not only in truly listening and being aware of others around you in the present, but to delve into our shared and separate pasts. Seek the common threads and the divergences.

As a writer and photographer, I’ve traveled on assignment extensively – Africa, Asia, Europe, throughout the Americas, even Antarctica several times. I’ve met people from all kinds of cultures, gotten to know them as individuals, shared their food within their homes, met their children and parents. Of course, I’ve also always read voraciously, fiction and non-fiction, history and philosophy… all manner of subjects and genres, from ancient myths to modern texts and futuristic visions. While I have a journalist’s critical mind which leads me to question all “facts” presented to me, I can have perfect suspension of disbelief when it comes to emotional or otherwise highly personal descriptions. That’s one of the reasons I can’t read horrific books or watch horror films. I can’t see pain without internalizing it. Nor can I write pain without cringing. Heartache and agony – as well as the full texture of personal, familial and cultural history — are among the stock in trade for a writer who wants to do justice to her characters, fully expressing who and why they are.

Besides, life is so much more fun, more interesting, if you can immerse yourself in a multi-dimensional, multi-cultural experience, not just as a writer but as a human being.

SW: What inspired you to approach this story through a small village in the Poconos? Why not Philadelphia or Chicago or Miami or New York? Do you feel like Jo could have had the same or a similar transformation in an urban area?

SG: Black Bear, Pennsylvania – the Pocono Mountains village in which “Jo Joe” is set – had its beginning in my relationship with my husband the author Daniel Grotta. So I’ll need to backtrack and diverge a bit to answer your question.

After living in Philadelphia, New York, London and elsewhere, and traveling to all seven continents and scores of islands, Daniel and I settled in the Poconos. Our town isn’t Black Bear, but it inspired an intellectual game we played, creating a fictional village that we planned to use as the setting for a series of stories. Daniel took it over first, for his novella “Honor.”

When I came up with the idea of “Jo Joe,” I knew immediately that it belonged in Black Bear. So I borrowed some of Daniel’s settings and characters (most notably Jeff Smith, the protagonist of “Honor,” and his curmudgeony father-in-law AH). I built on them, creating new locales and people, adding to their history, while further developing their interweaving stories. Daniel continued the process for his novel “Adam V” which is set on the outskirts of Black Bear (and which he finished just before he passed away a few months ago). Daniel left one more manuscript “Black Bear One” about the volunteer ambulance corps, which includes (among several new characters he developed) both Rabbi David and Joe Anderson from “Jo Joe”. I’ve recently started the research for another Black Bear novel “The Minyan.”

Daniel and I write quite differently. While we always discussed our works in progress, helping to brainstorm plot twists and character development, we had a line we never crossed when working in fiction. For any one book or tale, the person who was the author had complete autonomy over the story, the people, the underlying themes and so forth. The only rule is that we had to be true to any history or personality that was created in previous stories. So I couldn’t suddenly make Jeff Smith (who came of age during the Vietnam War era) a conscientious objector during World War II. Nor could either of us move AH’s car dealership off Main Street.

This literary “folie aux deux” was a dance between the two of us that allowed us to explore different kinds of human interactions, the implications of moral (or immoral) choices, and examine the fabric of human society on a small scale. I have several other Black Bear stories in development, plus I have Daniel’s notes for finishing “Black Bear One.” So the dance continues, even though Daniel is no longer here.

Could Judith (Jo) have found the same kind of self-understanding in a big city? I can only hope so, for her sake. However, the concentration of place and people that a village offers focuses the story, the way a magnifying glass can focus sunlight so that it burns a leaf. For me, the author, and for readers too, Black Bear doesn’t have the distractions of the larger world that we can hide in. Such is the nature of villages. Their ageless charm and the inevitable underlying tensions are what make them such suitable stages for storytelling. Mention a village, and as a species, we picture a concentrated geographical area reminiscent of small towns that have existed as long as humans have gathered to try to create a society larger than a single tribe.

Village life is a petri dish, a microcosm so very well suited to the kinds of stories Daniel and I enjoy telling – specifically character-driven plots in which complex, sometimes messy relationships play a major role. Of course, I set “Jo Joe” in Black Bear. It was the perfect locale for the story of Judith’s awakening.

SW: Your story seems, to me, to be very much about healing and forgiveness and the value of that process in becoming whole. In the real world, such instances of healing from the “isms” of our lives do occur. Jo’s struggle to hold onto her anger proves to be based in a large measure in her fear. She wants to leave Black Bear as soon as possible, to shred all evidence of her existence or the existence of her family. Where do you get your expertise in the psychology of healing? Is it all gained from intuition and interaction?

SG: I never thought of myself as an “expert” in the psychology of healing, and I thank you for that kind complement. It means a lot to me as a storyteller that is what you took away with you from “Jo Joe.”

My instinct is that you must be right that it’s “intuition and interaction,” because I’ve had no training in psychology. At least no more than any novelist. We (i.e. authors) carry so many characters within ourselves. No, I’m not schizophrenic (any more than other writers); it’s simply the way we create believable, flesh-and-blood fictional personalities.

I love all my characters, and I’m fascinated as I discover the layers of life and history that define them. Each one is based on an amalgam of people in the real world about whom I care very deeply. But they become individuals to me and are never simply symbols. It’s through their eyes that I see the scenes I write, including the conflicts that their opposing viewpoints inevitably create. The ability to see a scene or a story from various points of view certainly helps to provide new insights. It also fuels my deep abiding need to build bridges between people – both in my stories and in the real world.

I am honored that so many people have told me that my stories have helped them open up discussions about prejudice, preconceptions, tolerance and reconciliation. But I believe that comes from another type of collaboration — that between an author and readers. I often say the story I write is never the book you read. That’s because each reader imbues a book with her/his own past, fears and dreams. And it gives me hope for our world that, when they read my novels, they see their personal potential for healing and forgiveness.

About Sala Wyman

I’m Sala. I live in the Philadelphia area where an ever expanding community of extraordinary talent and camaraderie offers support for my efforts and the efforts of all aspiring writers. I’m working on a memoir infused with family, social change, spiritual studies and—love. Love is why I majored in and received a degree in Humanities. Love is why I write. Love is why I focus on what connects us, not what divides us. Please feel free to visit my blog: WORDS.