For those of us who came of age in the ’70s or ’80s, the thrill of purchasing that first record, or the memory of locking ourselves in our rooms to listen to one song over and over again, trying desperately not to scratch the delicate surface of the turning disk, is scored into our psyche. The connection between music and memories, especially in our youth, is a powerful one.

“There in the car, driving down Lake Shore and listening to ‘Livin’ on a Prayer,’ I had a moment of intense clarity. It was suddenly so obvious what I had to do. I needed to find that record. Not just any record. The record. The one with Heather’s phone number written on it. The exact copy I once owned, that represented something hugely important to me, some rite of passage into adulthood…And why stop with one record? Why not get all of them?…I wanted my records. My exact records. My literal exact records. I wanted them back. All of them. Or at least as many as I could find.”

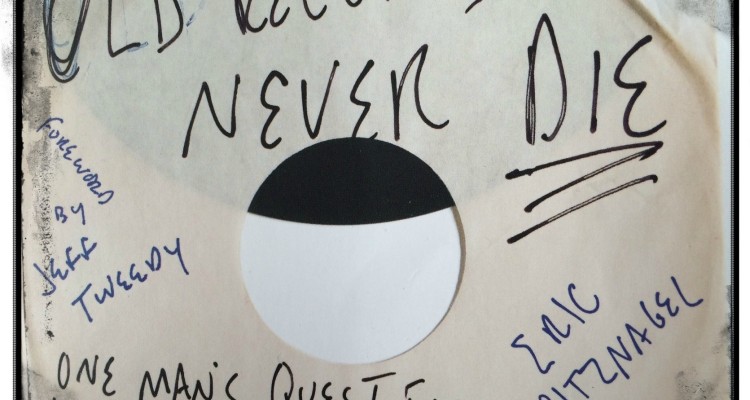

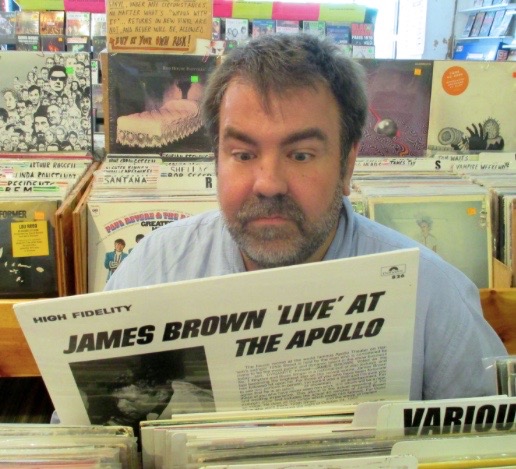

And so begins Eric Spitznagel’s odyssey to recover his lost vinyl. Searching for his records, Eric revisits moments from his past, connects with old friends and lovers, and meets strange and wonderful new characters along the way. With laugh out loud humor and moments of brilliant insight, Eric pulls us along on the journey with him. We discover that some memories may have been rewritten, youth can be gracefully surrendered, and the future is wonderful in it’s unpredictability. It’s a pleasure to feature Eric on BCB today!

Tabitha: You’ve written and co-written several books, mostly non-fiction humor. This memoir, while laugh out loud funny in many places, also contains some raw, personal moments. Was your writing experience with this very different from your other projects?

Eric: It was absolutely a very different experience. Some of the books I wrote in the late ’90s felt like stand-up acts. I did an entire book about junk food, for god’s sake. When you’re making jokes about Twinkies, you’re not really digging deep into the emotional well. With this book, it felt like I was finally writing something that mattered. Not to discount everything else I’ve done, but this was closer to my heart. It’s got my blood and guts on the page. Which makes it even more terrifying when it gets published. With the other books, there was never much on the line. If something didn’t sell or connect with readers, okay, we’ll try something else. But this one, it’s like dropping off your kid at the school bus stop for the first time, and you’re so happy that he’s growing up and heading off into the world, but you also don’t want to let him go, because what if there are bullies, and he gets teased, and he isn’t immediately embraced by his peers, and his crayon scribblings aren’t lauded by his teachers as Pollack paintings? It’s another level of vulnerable when you write something you care about this much and you have to let other people read it and decide if it’s something worth existing. My wife and I were just listening to the audio book version, which is fantastic, but it was so surreal to hear some actor read the things I’d written about us out loud. It was like hearing your diary read aloud by a stranger. There’s no way that’s not invasive. If you don’t squirm a little bit, you’re not really human, I don’t think.

Eric and his son Charlie

Tabitha: In some ways this was a story of letting go, or at least about making peace with the things we lose as we age. In one chapter, you talk about missing a Pixies concert because of adult obligations. “Between the two options, I’d made the only choice worth making. But you still feel the loss.” For me, this statement perfectly captures the essence of embracing adulthood – that moment when you recognize you aren’t the teenager or the twenty-something you still think you should see in the mirror! But to really relate to this sentiment, you have to be a certain age. Were you mindful of a particular audience when you were writing?

Eric: I try to write for one person. I don’t know exactly who that person is, but it’s definitely just one person. I like that intensity of focus. The kind of writing that really moves me these days is when it feels like you’re having a conversation with somebody at a party, and you don’t even know this person but you just started talking to them, and you’re both on your third cocktail so maybe you’re sharing things you wouldn’t have been sharing otherwise. That’s the kind of intimacy I’m shooting for. You’re a little buzzed and you’re talking to a stranger and you’re like, “I know I just met you, but I need to tell somebody how Willie Nelson songs make me sad about my dead father.”

Tabitha: I love the scene when you meet with your ex-girlfriend Heather, all these years later, and play her old Bon Jovi record for her in her living room. I love that you reconnected with her, but I love more that the encounter is filled with the gift of perspective. The theme of memory and perspective seems present throughout the book. Was this intentional, or did it develop out of your experiences along the way?

Eric: That’s the amazing thing about living a memoir as you’re writing it. You’re constantly riding that line between “I can’t believe this is happening” and “This is an abyssal failure. Why did I ever think there was enough here for a book?” I sold the premise to Plume solely on, “This is what I want to do, but it’s probably not going to happen this way, but wouldn’t it be fucking awesome if it did?” It was all good intentions and apologies in advance. I knew I wanted my records back, and I knew the record store where I sold most of them had gone out of business. That’s all I had. That’s enough for maybe 20 pages. After that, who the hell knows? The whole book could’ve just been me flipping through boxes of records, and I never find anything and nothing meaningful is learned, and it’s just “Well, that was a colossal waste of time. Sorry, everybody!” Showing up to see Heather, I had no idea what I was in for. I hadn’t seen her in two decades. It could have been an awkward conversation, but nothing worth writing about. If there’s one thing I learned from years of being a journalist it’s that you can’t orchestrate a story. You go in with a question, and you just see where it takes you. Failure is always an option, and that’s what makes it exciting. For every chapter in the book, there were maybe 20 or so dead ends that I didn’t write about. What ended up in the book are just the highlights. And I got lucky. When it clicked, when I stumbled onto a narrative arc, it was like an out of body experience. You try to stay in the moment, but the writer in you is giggling, amazed that life can sometimes play out more perfectly than fiction.

Tabitha: Was there a favorite moment for you on this journey?

Eric: The final few chapters. When I’m listening to records with old friends in my childhood home. I don’t want to give too much away, but that was like church for me. It was like a gospel church where you feel connected to something bigger than yourself. It was weirdly cathartic. You’ve got three guys still mourning their dead dads singing old punk rock songs in an empty house that was filled with shadows and memories from their childhood. Oh, and eating cereal that hasn’t been fresh since Jimmy Carter was president. How is that not going to be a transcendent experience?

Tabitha: While some of the story is about looking back, your insightful wife points out that you chose to embark on this quest before moving forward – before accepting the office job with the regular hours, the steady pay, and the slaaaacks! (Read about Eric’s issue with slacks here: www.EricSpitznagel.com). What’s been the biggest upside to joining the dark side?

Eric: The most obvious upside is that I don’t have to wear pants. I thought I would have to, but I really don’t. I’ve worn shorts almost every day since becoming a full-time Men’s Health employee. Maybe a week or two into my first month, I came to work wearing pants, and my boss made me roll them up into makeshift shorts. “I didn’t hire a wearing-pants-to-the-office guy,” he told me. Sometimes it’s the little things that make you feel at home.

The down side—and maybe it’s not a down side—is that I’m suddenly surrounded by people who have more than a passing interest in their health. In Chicago, the writers I socialized with were always just a rejection email away from drinking at noon. But the Men’s Health staff, wow, sometimes it’s like being on another planet. I remember my first week on the job, I went to cafeteria and one of my editing colleagues showed up with wet hair, and I was like “Is it raining outside?” And he said, “No, I just got back from working out.” And I said, “Working out what?” And he said, “Working out as in exercise.” And I said, “On purpose?” And he said, “What do you mean?” And then we just stared at each other like the other person was an alien. That actually happened to me! I’d never encountered people who had wet hair because they’d been exercising of their own free will.

Tabitha: You’ve had a long and varied career as a writer. Can you talk a little about your professional path? At one time you wrote plays…

Eric: That’s right. My original goal was to be the non-Catholic Christopher Durang. I wrote plays that got produced at tiny Chicago theaters in bad neighborhoods. The plays had mildly funny titles like “Grandpa Ruins Christmas” and “Nothing Cute Gets Eaten,” and nobody ever showed up, because the theaters were always next to crack houses, or the show times were at 10pm or later and there were hookers or drug dealers loitering outside the theater, and even my friends were like, “Nope. Sorry, can’t do it.” But one of the actors in those plays became my writing partner, and we ended up writing for small indie mags in the city, and eventually Playboy, which was still based in Chicago in the early 90s. My entire writing career has been an accident. I couldn’t trace a trajectory that any fledgling journalist could possibly learn from. It’s all been a random series of events that inexplicably led to what I’m doing today. The only consistent has been that I wanted to be a writer. I didn’t care if it was writing plays that nobody saw in ghetto theaters in Chicago, or writing adult film scripts in LA (which I actually did for a year), or teaching sketch comedy at the Second City (which I did despite having no idea how to write sketch comedy), or interviewing hundreds of celebrities for Vanity Fair. Whatever the next opportunity was, I was like, “Okay, I guess I’m doing this now.”

Tabitha: The list of people you’ve interviewed is impressive, and I have to ask…was there a standout favorite?

Eric: My favorite was probably Merle Haggard. And not just because he recently passed away. I have a weird fondness for old guys with endless stories about their hilarious mistakes. There’s nothing more mind-numbingly boring than talking to a 20 or 30 year old celebrity. They’re just not good storytellers. Even if they’ve had some amazing experiences, they don’t know how to spin a yarn. Maybe they’re just too protective of their image, or they feel like they’re sharing too much and they should be more mysterious. I’ve never interviewed a 20 year old who made my stomach hurt from laughing, or left me speechless. But you talk to somebody like Merle Haggard, or Burt Reynolds, or John Cleese, or Danny DeVito, or anybody who’s got some serious mileage on the life speedometer, and you forget that asking them questions is your job. At a certain age, you just don’t give a shit anymore what people think. Or maybe you get hindsight on your life, and you have a sharper perspective on what was meaningful and what was forgettable. I really don’t know. But I’d rather listen to Willie Nelson ramble about nothing in particular while he’s smoking a joint the size of a baby’s arm than pretend to be interested in whatever the hot young actor of the moment has to say.

Tabitha: Let’s talk writing craft for a minute. A memoir is obviously different from a novel, but you still have to create flow, balance exposition with dialogue, and keep the reader engaged, just as any fiction writer must. How did you choose where to begin this book? How did you decide on the structure? Was there ever a point where you wanted to toss the whole thing?

Eric: You figure it out after the fact. It’s really an extension of journalism. If you’re doing your job the right way, you don’t go into it with a str ucture. You can’t dictate the terms. You just come in with a general premise, and you ask a lot of questions, and you let it unfold the way it’s going to unfold. Going into this, I had a lot of ideas about what this book was going to be. And trust me, none of them were even close to accurate. Everything I thought was going to be a dead end turned out to be gold. And everything I could see so clearly in my head, that I was convinced would be brilliant storytelling, it all fizzled. When you’re writing about your own life as it’s happening, you really can’t predict how it’ll go down. You just try and pay attention, and you write down the good stuff. Weird and wonderful things can happen if you get out of your own way.

ucture. You can’t dictate the terms. You just come in with a general premise, and you ask a lot of questions, and you let it unfold the way it’s going to unfold. Going into this, I had a lot of ideas about what this book was going to be. And trust me, none of them were even close to accurate. Everything I thought was going to be a dead end turned out to be gold. And everything I could see so clearly in my head, that I was convinced would be brilliant storytelling, it all fizzled. When you’re writing about your own life as it’s happening, you really can’t predict how it’ll go down. You just try and pay attention, and you write down the good stuff. Weird and wonderful things can happen if you get out of your own way.

Tabitha: Do you have any interest in writing pure fiction?

Eric: Honestly, no. I had an interest when I was younger. I wanted to be like Kurt Vonnegut and write beautiful novels that had more truth than anything I read in non-fiction. But I’m losing interest in fiction as I get older. I don’t know why. Anything fictional feels like a sitcom to me. I’m more fascinated by a great documentary than I am by a Hollywood movie. I can’t read novels anymore, because it always feels like I’m missing out on something. Why would I listen to a made-up story when there are so many bizarre, hilarious, “that seriously happened to you?” stories in the world. That’s no disrespect to fiction, it’s just where my head is at. I want to know what people actually experienced, because truth is always stranger than fiction. It really is. People have lived weirder lives than anything imagined in literature.

Tabitha: Congratulations on putting a new book into the world! I know this isn’t your first rodeo, but do you have a release day tradition? Do you drink a bottle of champagne? Hide in your room for the entire day?

Eric: Ha. I really don’t. But for something like this, which is something so close to my heart, it was enough just to get the box of books from my publisher, and to open it up with my family, and to watch my now 5-year-old son hold up the book for the first time, and flip through it, and look at me with a perplexed expression and say, “Daddy, it’s so… small. You spent two years making this? Shouldn’t it be bigger? This is like a baby book.” I’ll save you the trouble. No, it’s not the first time I’ve heard, “Shouldn’t it be bigger?”

Eric Spitznagel has authored six books, edited several humor anthologies, and currently writes for magazines including Men’s Health, Esquire, Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, Playboy, and Maxim. You can find visit Eric’s website www.ericspitznagel.com and follow him on Twitter @ericspitznagel.